Boozhoo, indinawemaaganidog! Aaniin! That is to say hello, all of my relatives! Welcome to another edition of An Irritable Métis. I’m at my desk marveling at the early afternoon light outside my window. Not the light of dagwaagin – though on a gorgeous day like today that is part of it – but because while I was away on Saturday maintenance crews came up my street and cut down two magnificent cottonwoods from the south edge of my yard. It sucks. It technically isn’t my yard, I don’t “own the land,” but I’m responsible for maintaining it. And with no warning or explanation the people who do “own the land”1 sent someone out to remove the trees. They were perfectly healthy and only just now beginning to change color and now they are gone and all that remains are big stumps. I’ve since learned that cottonwoods are illegal in this street-side context in many places, which might be the case here in Missoula County too, but to suggest that over the nearly ten years I’ve been here I haven’t formed a relationship with the trees would be incorrect. It makes me very sad and I miss them. On an unseasonably warm day as today I feel the loss of their shade. I can’t imagine what summers will be like. I’m reminded of this poem by the great Tess Gallagher, which I would like to dedicate to these fallen relatives, and all the nests no longer there.

In happier news, I want to thank everyone who donated to my friend Andō. You really rose to the occasion and I am so grateful. I know Andō is too. What a wonderful community you are. You prove over and over with your support and kindness that the world isn’t populated entirely by asshats.

Native survivance stories are renunciations of dominance, tragedy, and victimry.

– Gerald Vizenor

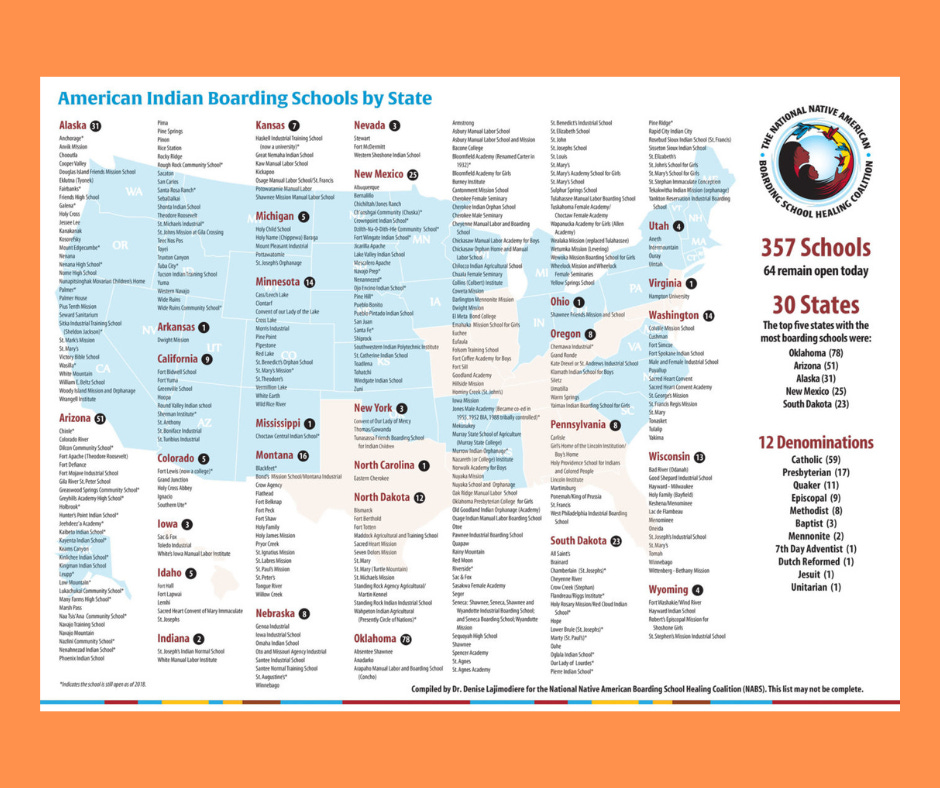

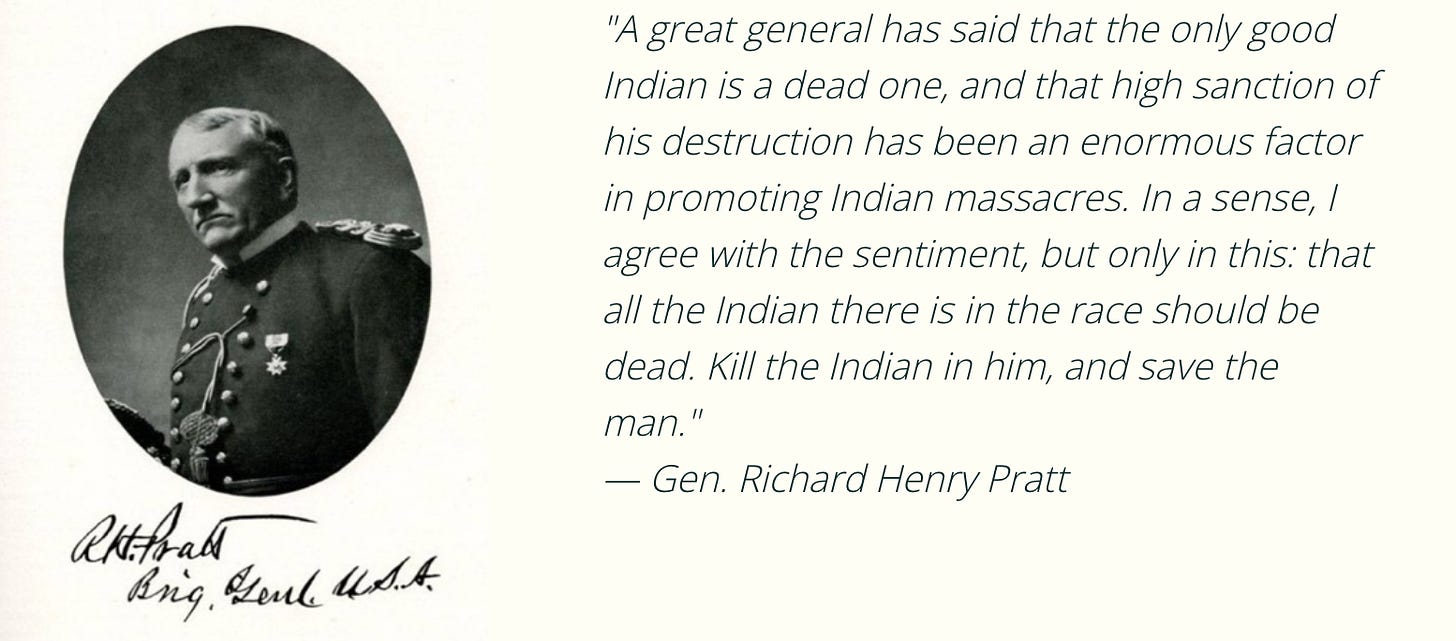

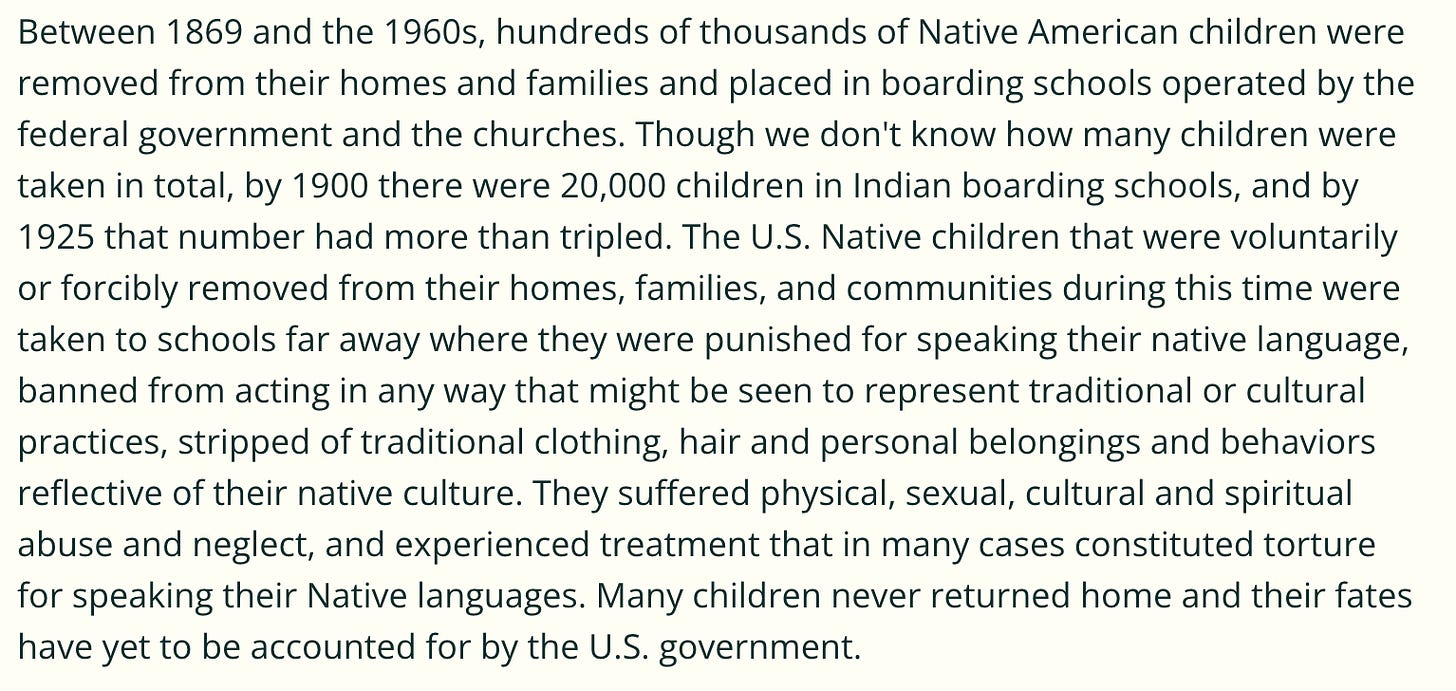

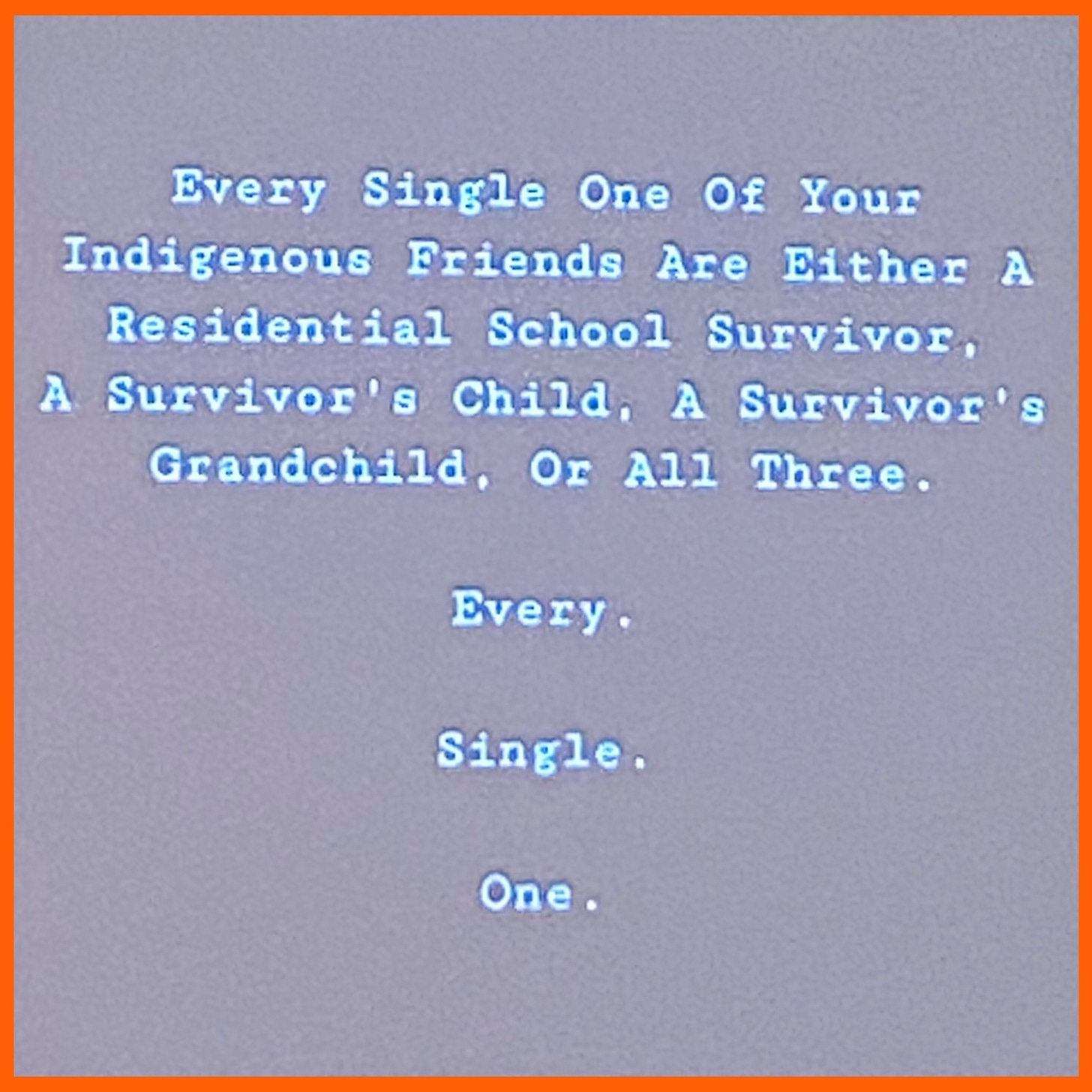

Do you remember when you first learned of Indian boarding schools? Was it in elementary school? High school? University? Was it a history you were taught, or something you learned on your own? When did it become known to you maybe not so much as a thing that happened, but as a story of horror? Do you still not know? If you don’t it’s certainly not your fault. For as many affected generations still struggling to recover there are generations of people, powerful people, intent on keeping it covered up. Especially if you are from the United States, where we do everything we can to try and keep ourselves convinced that we are a force for good in the world, when we are the complete opposite. After all, it was the United States who really set the bar on this kind of thing.

Take a look at what the United Nations Office on Genocide has determined qualifies as genocide and then think about what the U.S. has done to Indigenous people. Just because the determinations weren’t defined until 1944 doesn’t mean the U.S. wasn’t doing them. We have inflicted every so-defined bullet point on Indigenous people, and continue to, if less overtly in some cases.

Still, would we even be talking much about boarding schools if not for those first unmarked graves discovered in Canada just over a year ago? Or after another 750 were found a few weeks later? There have been more, on both sides of the Medicine Line, and no doubt more will be found … and not found. And we still hardly ever talk about it. People just don’t really care that much about Indians. Never really did, still don’t really, for all the lip service. North American governments say all the right things until, for example, they need to build a pipeline or dig a mine or hide radioactive waste.

I am reflecting on all this today because of a conference I attended at the University of Montana last Friday, September 30th. The conference was called, “Boarding Schools: Remembering our Resiliency and Shared Knowledge for Trauma Informed Learning.” A heavy topic indeed and appropriate for the day; September 30th being the National Day of Remembrance for Indian Boarding Schools, or “Orange Shirt Day” as it is known in Canada, where it started. There were many orange shirts among the attendees, and elsewhere on campus, including the one stretched across my torso. There was much laughter and joy at the event, but do not misconstrue the spirit of the day as celebratory. We would much rather not even have to think about it, but since boarding schools happened and remain unreconciled, we must.

I was overwhelmed as ever to be in the company of so many smart, brave Indians. The majority – both as attendees and as presenters – were women; mostly middle-aged or older, but plenty amoung the younger generations as well. So much gorgeous beadwork, so many scintillating ribbon skirts. A significant turnout of people from all over the state and from other states, and familiar faces I’ve come to know only through attending gatherings such as this. Not to mention the non-Native people involved in giving the speakers a microphone; people who are devoting their lives and careers to truly being allies to the cause. I don’t say that lightly because so many people want to call themselves an “ally” until the work becomes grueling and overly challenging to their worldview. I have so much love and respect for the folks walking the walk even as they face the occasional sneer from Native faces who don’t see their effort. They prove our relationship as relatives across all bounds of culture and language and skin color. We are all in this together, and we must work together if there is hope for any of us.

So yes, the gathering was glorious. It was also sad.

I heard elders speak of their experience as boarding school survivors. It was heartbreaking hearing their stories, seeing them relive moments fresh in their memories of events that occurred more years ago than most of us have been alive. I heard brilliant scholars and social workers explain the layers of trauma all of us carry as a result of federal Indian policy. How we are still reconciling changes that began 500 years ago within the very cells of our bodies, and trying to overcome obstacles the dominant culture urges us to just “get over.”

I learned of concepts like “Indigenous Theory & Decolonizing Methodology.” I learned more about epigenetics, and the effects of ongoing and cumulative trauma. I learned the stages of colonialism and how they have specifically played out in North America, and that 80% of the world has been colonized. It was a lot to take and it was difficult. Clearly it is still settling in my mind because I’m not articulating any of this experience very well. There are thousands of words to be written but I am settling on just these few because I can’t tell you. I’m still reconciling for myself what this all means and how it is reflected in the struggles I have with the world that really aren’t supported by any personal experiences I’ve faced, yet they are real.

It made me rethink a lot of things. A land acknowledgement sounds differently from the lips of an Indigenous person. Talk of resilience does too, a word veteran readers will know I struggle with. If nothing else, the conference was a good experience in being in an environment surrounded by people I could relate to, who can relate to the things that set me off so easily. It felt safe, and how often do we – any of us who don’t fit into the “default system” built primarily on wealth, privilege, gender, sexuality, and skin color – get to feel that way?

“The default system was not build for us.”

– Turquoise Devereux (Salish/Blackfeet)

There are times it is almost too much to bear, and yet we do. Times the grief seems too much to face and yet we must; we face it and experience it and honor it and then put it in our packs and carry it with us because it isn’t anything that ever really goes away anyway. Nor can we unload it on anyone else; it is our burden, and even if we desired it this is no time to collapse and wait for our time to expire. An overwhelming abundance of our relatives faced unimaginable hardship just to ensure that we would have the opportunity in this world to gather and reflect and talk and weep and make plans to strengthen our future. To make certain that what has happened to us never happens again to anyone, anywhere. We owe our steadfastness to our ancestors. We owe them strength, and love, and fury. We owe them loud voices where theirs had to be still.

By the final session and its closing remarks the crowd had diminished significantly. It was late and the day had been long and I don’t blame people for leaving. A storm was building outside. Those of us remaining gathered in a circle of sorts; the shape of the open space we had for ourselves didn’t lend itself for much of a round shape and yet, in the darkened room, it felt more intimate than at any other moment during the conference. There were smiles and hugs. There was a closing prayer from Laura Gervais, a Kainai/Blackfeet elder and boarding school survivor whose words had opened the conference. Leaning on her walker Laura spoke herself into tears, and then she prayed for all of us. Her words seemed to unfold over minutes and generations simultaneously. I don’t know what she said; she spoke in Blackfeet. Yet I understood perfectly.

But don’t live here, of course

Aghh! I'm so sorry about the trees. That's horrible. You know how I feel about trees.

I'm beginning to think we're seeing a second wave of colonization, where the people who live here now, however they got here, are losing whatever agency they might have had over the land where they live, and therefore over their own lives.

I say that as a great-grandchild of white settlers, feeling conflicted about my own luck in owning a handkerchief of land. Watching the housing crisis escalate while private equity cleans up. Watching in horror as the wealthy elite commandeer this state for their own after dividing the current inhabitants into warring tribes so that they are completely powerless to fight back.

Thanks for your loud voice, Chris. I'm not sure when I first heard about Indian boarding schools. I for sure didn't realize until now that it went on for a century. Howwwwww do we make sure that doesn't happen again? The cyclical nature of history terrifies me.

Canadia resident here. I learned about the schools in grade five, in 1995, a year before the last one closed. But even then, they were talked about very much in the past tense and white-washed (in both the covering over and the racist way) as a funny little mistake rather than an intentional systematic part of the British colonial government's commitment to genocide.

My adult learning was significantly different as it occurred to me that my Michif and Cree speaking great-grandmother was likely taken into one, but I'd probably never truly know because Métis children were treated so inconsistently by a system that approaches human identities as binaried and without any nuance. There are not great records, although that in itself is the point, of course. I don't share about this often, but when I do I point out to people that I am the result the system was aiming for—cut off from one whole limb of my family tree and lineage, uncertain of what my non-white ancestors lived through, survived, and didn't survive, while fully aware of my white ancestry and able to find records stretching back to the 1300s.

It's something I visit in my own writing again and again.

I appreciate this post so much, and how it captures the particular grief that comes from not knowing the specifics of what white supremacy colonialism destroyed, as well as the reality that colonialism is not a thing of the past.