On a Saturday afternoon I made the trip up to Seeley Lake to attend a presentation by the environmental writer Doug Chadwick in support of his latest book, Four Fifths a Grizzly: A New Perspective on Nature That Just Might Save Us All. I have been a huge fan of his work since I read The Wolverine Way, possibly one of my desert island books as it relates to wildlife and natural history.

It was a glorious day to be out. Early in the day it was misty, with shreds of cloud clinging to the rocky outcroppings bordering Highway 200 north, the Blackfoot River still choked with ice. Frost painted every limb, every pine needle, and the air gnawed exposed flesh with cold. Later, the sun was out and almost painfully bright. It hurt to look at the brilliant white of the peaks of the Swans but I did anyway. One couldn’t ask for a better headspace for thinking of wild things.

We are all wild things if we remember to be. In a series of linked essays, Chadwick’s main argument in Four Fifths is that humans are deeply-connected genetically to everything else on the planet—literally everything is so connected—and that recognizing this truth is key to our understanding that our continued disregard of—and harm to—the world is a self-destructive act of harming ourselves. Chadwick is a wonderful writer and storyteller and his message is an important one. Personally, it all plays perfectly to my current “we are all in this together” trip.

One particular segment of Chadwick’s presentation grabbed my attention. He was talking about the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative (Y2Y). The Y2Y is a joint Canada-U.S. not-for-profit organization and the only organization dedicated to securing the long-term ecological health of this entire region. The organization’s vision is “an interconnected system of wild lands and waters stretching from Yellowstone to Yukon, harmonizing the needs of people with those of nature. Recognizing communities need equal opportunities and rights to thrive, Y2Y seeks to support human diversity, equity, inclusion; and environmental and social justice, and to oppose actions and policies that undermine these principles.”

The region referred to is a vast 2000 mile stretch from Yellowstone National Park all the way north to the Canadian Yukon. The goal is to connect protected areas across that landscape so that wildlife are also able to move across a wider swathe of territory. Chadwick shared a map similar to this one (which I swiped from the Y2Y website), from pre-1993:

You see the region and the green protected areas, which look like islands. Places like Yellowstone, Glacier, etc. When these areas were first established, there was still some potential for their inhabitants to roam abroad, but that has changed (notably, the yearly “culling” of bison who migrate out of Yellowstone, for example; likewise, and most recently and horrifically, the decimation of an entire wolf pack because of Montana’s ruling class’s political cruelty and soulless evil).

In Four Fifths, Chadwick describes the current situation thusly:

In twenty-first-century settings, animals traveling beyond refuges often struggle to find habitats with adequate food and security in adjoining terrain. Their chances for survival and reproduction there drop faster by the year. Increasingly isolated, the wildlife inside reserves becomes more susceptible to inbreeding and whatever natural disasters sweep through. Now add pressures from a global environment in the throes of a strong and accelerating warming trend. We already know that species on oceanic islands face an elevated risk of extinction. We also know that the smaller an island is and the farther away it lies from other areas with wildlife populations, the less variety of life it is able to support over time.

Point being, these animals, these relatives, need more of their original range returned to them—and corridors connecting each to the other—so that they have a greater chance to survive. To thrive, even. It is a no-brainer if we want these species to have any kind of future. The collapse of an “umbrella species”1 like the grizzly bear (also currently under attack by the same shitass Montana politicians) leads to a domino effect of collapse of other species. This is connection. It is an idea foundational to Big Conservation, a subset of what I have come to think of as the Nonprofit Industrial Complex.

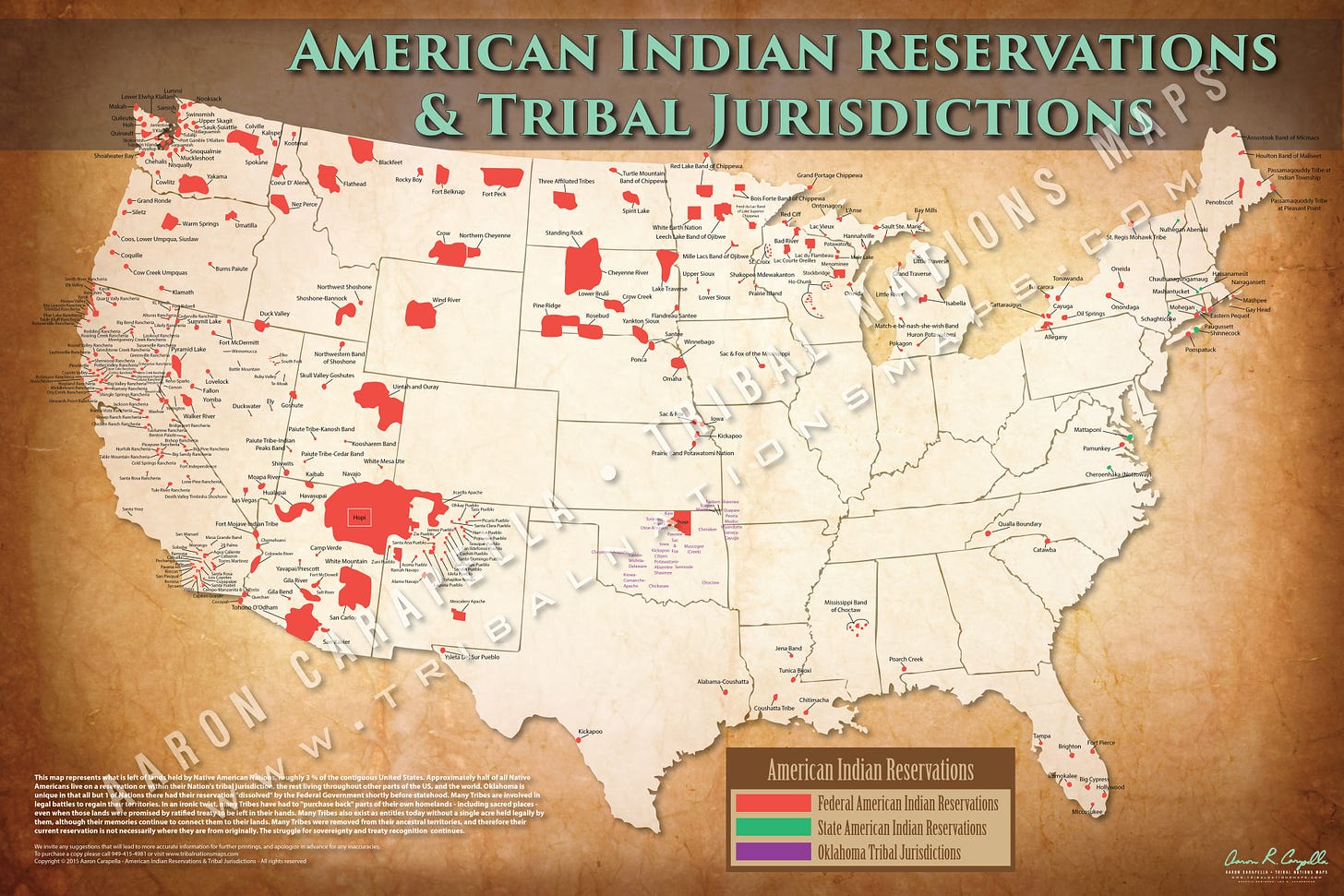

The same should be said for people. For example, here is a map of Indian reservations in the United States:

Doesn’t look so different, does it? A map of Canada’s tribal reserves would present similarly. Little islands across a landscape that tribes once inhabited from coast to coast.

It is heartbreaking, both maps. What you are seeing in the reduction of wildlife ranges is mirrored in how Indigenous people were driven near to extinction and then shoved aside into “protected” ranges: i.e. reservations. One important difference though is that all of those islands of “protected” habitat for wildlife first had their Indigenous inhabitants eradicated before they were set aside for conservation (though in many, if not most, cases conservation was only secondary to the effort).

What are some of the other similarities? For starters, Indians on reservations long faced the threat of death if they were found wandering outside of their borders. The history of my people, the Little Shell, and how we became landless for more than a century-and-a-half relates specifically to those ancestors who were “off the reservation” and were therefore disenrolled during the final days of more blatant land grabbery.

Here’s another one. The charismatic predators that hateful criminals like our Montana governor and his ilk get their jollies murdering are also the first animals people tend to gravitate toward for mascots, for postcards, for “cabin chic” and all that lamentable capitalist garbage. Just like people do in the appropriation of Indian imagery, Indian art, Indian spirituality, all while doing next to nothing to prevent the eradication of Indigenous people. This doesn’t just speak to North America either, it is a global phenomenon.

Now for a dissimilarity in wildlife vs. people. While much work is being done to preserve wildlife genetically, the same can’t be said for Indigenous people. Blood quantum requirements—the unscientific and utterly bullshit practice of determining percentage of “Indian blood” for the purposes of tribal enrollment—are a colonial weapon slowly driving Tribes to extinction. This is also an effort embraced by the shortsightedness of scores of “me first” tribal councils across the country and their duped citizens, all while being patted on the hands by greedy lawyers bent on genocide.2 It is that simple and that imminent. First the land was taken and now processes implented decades ago churn away at the eradication of Indian people altogether.

Here is a map of the same Y2Y region circa 2018:

You’ll see the darker green as additional land that has been protected to serve this Y2Y project. There isn’t much, but there is some, and that is hopeful. But is it enough? Hard to say.

I am all for these conservation efforts but I also view them with a healthy dose of side-eye. When thinking about impacts on people, the organizations doing this work must think beyond impacts on white people jobs, white people recreation, and white people property rights, and I’m not convinced enough of them do so. Effort must be made in returning land to Indigenous people for the same reason land is being protected for wildlife. It is critical to the continued existence, and restoration, of Indigenous culture and lifeways.

From its home in Regina, Saskatchewan, the fiercely independent publication Briarpatch devoted an entire issue to “Land Back” back in the fall of 2020. It is well worth checking out. Last spring, the great David Treuer wrote of returning the National Parks to their original inhabitants in a wonderful piece for the Atlantic. Local to me, the CSKT regained control of the Bison Range one year ago, being returned land that was initially stolen from them. Anna V. Smith for High Country News has a great piece about that HERE. It is an essential read; here is an excerpt:

Opposition from non-Natives is common when it comes to returning land to tribal management, said Krystal Two Bulls, Northern Cheyenne and Oglala Lakota, director of NDN Collective’s LandBack campaign. Two Bulls, who is from Lame Deer, Montana, sees the return of the National Bison Range as emblematic of the long endeavor to shift the stewardship of public lands — many of which were taken illegally — back to tribes. Similar conversations are happening over Bears Ears National Monument in Utah and Gwich’in lands in the Arctic. It’s a generational battle, but, Two Bulls said, “More than any other campaign that I’ve worked on or any other organizing space that I’ve been in, Land Back is one of the ones that holds the most hope.”

This is critical. I love what the opportunity to be stewards of the land again would do for generations of Indigenous people. Reiterating that Y2Y vision:

Recognizing communities need equal opportunities and rights to thrive, Y2Y seeks to support human diversity, equity, inclusion; and environmental and social justice, and to oppose actions and policies that undermine these principles.

Equal opportunities. Rights to thrive. Inclusion. Social justice. Big, bold ideas, yes … and essential ones. It is important that conservation organizations make Indigenous people and #landback a priority, and remain committed to these values. Anything else is just the same old story. It’s just more colonialism.

What is an umbrella species? Y2Y says: "Generally, it refers to situations when protecting what a single species needs also protects multiple nearby species (and those further down the food chain) that share the same habitats or ecosystems. When Y2Y works to conserve grizzly bears, we help conserve all species that 'fit under their umbrella'."

Some go so far as to actively disenroll their members for various nefarious reasons. I’d elaborate but I may write something more specific to this in the future. Suffice to say, the sooner Tribes revamp their constitutions to throw out blood quantum requirements—and maybe the idea of “constitutions” in the first place, the mere word reeks of colonialism—the better. There is no future for Indian nations as long as BQ exists.

I’ve never looked at the Y2Y and reservation maps alongside each other like that. It’s such a great illustration, especially when thinking about previous connectedness before colonization.

Great piece, Chris. Land back feels like just a start …

Thanks. Of course, I missed your perspective in my old white lady mind. Doug Peacock is my friend and I’m almost always in agreement with his ideas. Your piece adds another important layer to this one. I’m shaking my head at my own blindness. This is so much bigger than I knew. Just thanks. Looking forward to meeting you in YNP a couple weeks.