Boozhoo, indinawemaaganidog! Aaniin! That is to say hello, all of my relatives! Welcome to another edition of An Irritable Métis. I want to begin this newsletter with the joyful (and late) announcement that our efforts through April to raise money for this summer’s workshop in June on the Main Salmon River with the Freeflow Institute was a triumphant success. The goal was to raise enough funds to provide scholarships for two Indigenous folks and instead we raised enough for FIVE! Isn’t that great? You people really stepped up and I am incredibly grateful. The next step is getting people to express interest in participating. So if you are Indigenous (enrolled or not, IDGAF) and think you might be able to make it happen, CONTACT ME. There is even some potential for travel reimbursements to help you get here so don’t let that be a barrier to you. Meanwhile I’m putting the word out to everyone I know who might be able to make some suggestions. If you are one of those people, help spread the word if you like! Time’s a wasting!

Field School

There is a story I’ve read multiple accounts of from various perspectives of people who allegedly witnessed it. It’s from 1879, and a train of Red River carts pulled by oxen are squealing across the prairie from where they crossed the Missouri River at Fort Benton and headed south into what is now called the Judith Basin in Central Montana. These are my ancestors, and for the second time they have been chased off the Milk River farther north and are now making their way south, essentially at gun point, in an effort to cling to the only life they’ve ever known. That life is centered on hunting buffalo and it is here in this wide land that the last dwindling remnants of the big herds can be found. And they do find some, and that is where the story begins.

When this collection of twenty-five families encounter the buffalo, a number of men ride out on horseback to run – hunt – them and mayhem ensues. In their flight from Métis rifles the buffalo get in among the cart train, scattering people like tourists in the Lamar Valley, overturning carts, raising a tremendous dust cloud. The story is always relayed as almost comical, and it probably was amusing – once the dust settled and no one was injured – to watch. I do wonder about the success of the hunt, and also wonder how many of those hunters ever actually got to run buffalo again? It was a hard time there in the waning days of a tradition that had been a way of life for so many people for generation upon generation.

I’m thinking about this story because a few mornings ago I hiked up onto a hilltop and looked out in every direction and wondered if my eyes were landing on the location this drama unfolded. It’s not impossible to think that I might have even been standing in the very spot one of those observers was.

I’ve just emerged from a few days of sleeping on the ground1 out in the vastness of the High Plains. Every day the wind was unrelenting until dusk when it finally subsided. I went to sleep each night to the cacophony of what sounded like millions of loud boreal chorus frogs. I was surrounded from below by hundreds of prairie dogs who emerged every morning to spend their day whistling and wheezing and scuttling about. For the first time ever I saw a burrowing owl and I watched long-billed curlews chase crows like kingbirds after bugs. I took a long, unplanned nap flat on my back out in the middle of it all feeling as if I were the last person on the planet and, on waking, was mildly disappointed to realize I wasn’t and that I still shared this magnificence with copious sons-a-bitches who take it all for granted. Or, worse, gaze upon it and see only a wasteland to be exploited. It is anything but that.

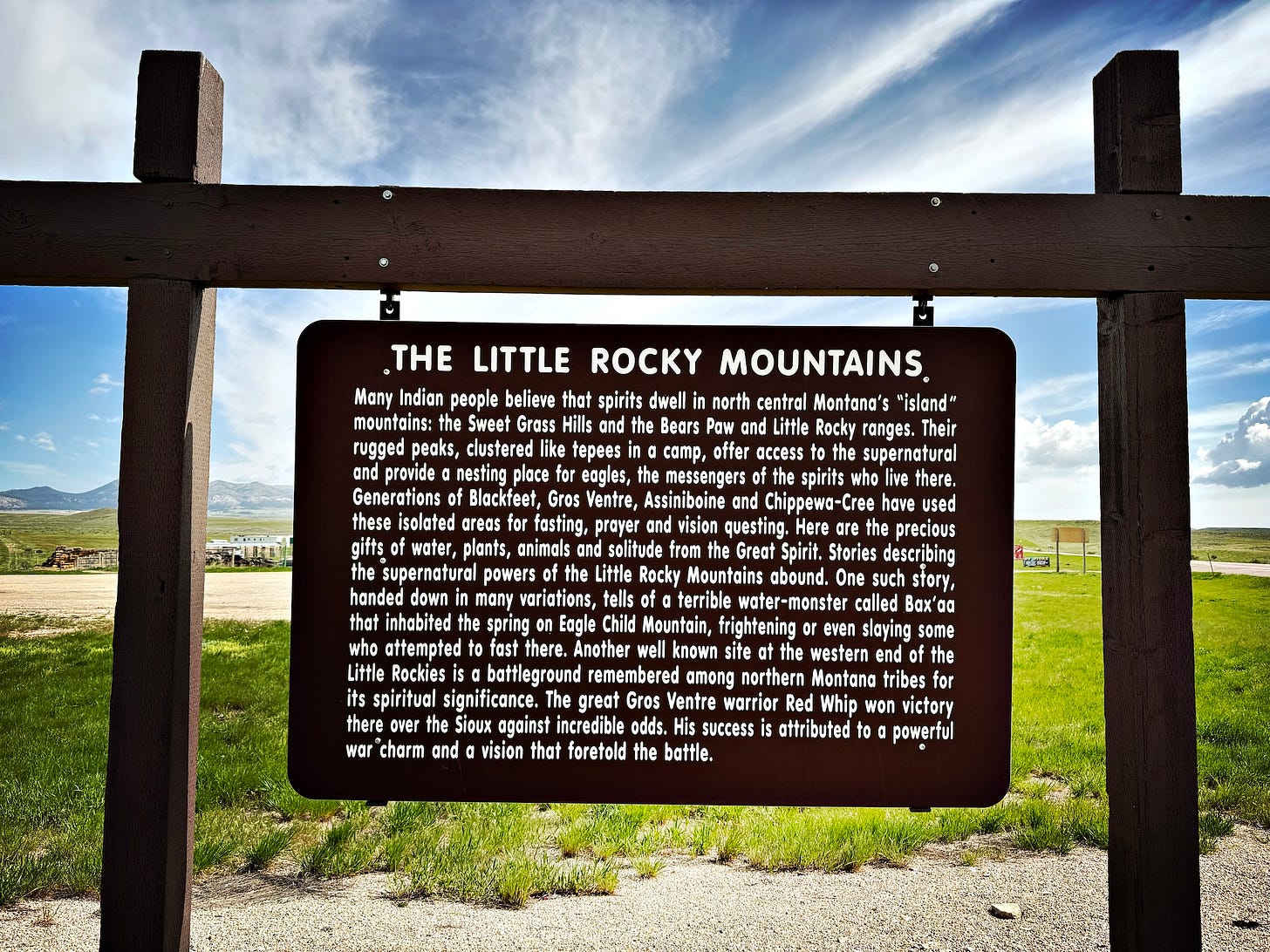

I’m happy to say there weren’t any of those SOBs immediately present, though. Quite the opposite. I was a guest at the American Prairie Field School and got to talk poetry and storytelling with a group of 7th graders from Poplar, Montana, on the Fort Peck Reservation. Over my days on the prairie we engaged in playing traditional Native games as taught to us by the Aaniiih Nakoda Tours folks from the nearby Fort Belknap Indian Community.2 We also did nature walks, played other games, ate bison sloppy joes and Three Sisters Soup, and disappeared a considerable quantity of s’mores.

The point of Field School isn’t just to teach young people about the ecology of the prairie. It is also to engender a love and appreciation for the landscape and for the natural world, for lack of a better description, in general. To immerse them outdoors in ways that maybe they haven’t had opportunity to be. To help them reconsider what “nature” really even is, and what their connection to it is. It’s the same reason I am passionate about trying to get people of less privilege into the various types of workshops I do with adults. Immersion, especially for people who haven’t experienced it, is often life changing. I’m a huge advocate of it for everyone.

I was at Field School mostly as an observer. The bulk of the time with the kids was handled by a pair of young, energetic instructors from MOSS, or the Montana Outdoor Science School based in Bozeman. They did a great job and I was happy to learn plenty from them as well. I wasn’t as involved in everything as I usually am. I didn’t really connect with the kids in any significant way, and I don’t recall a single one of them interacting with me for any reason beyond answering direct questions when I was addressing them. Which is also fine but also a little disappointing. I have less idea than usual about whether anything I said to them actually reached them. I hope it did.

I loved letting other people lead the way. Listening and watching and not talking was good for me. It’s always good for me and I’m grateful I’ve trained for years to be reasonably capable of it, even as I fail as often as I succeed. I enjoyed seeing the kids receive instruction, enjoyed watching them learn. Enjoyed their curiosity and their intellect. I was largely invisible to them and I was able to hide in plain sight and listen to their interactions when they assumed no one was around. It was a great place to be. These are people living lives entirely different from mine and it would be the height of arrogance for me to assume that I would be incapable of learning anything from them.

I spent a lot of time reflecting on what I could offer such people if an opportunity like this ever presents itself again. I’m reflecting on all that now and feeling a little wistful; I’m reflecting on how the students at Field School were taught. The instruction they received was valuable, certainly, and delivered with kindness, but it was still largely couched in settler conservation. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if the MOSS instructors were joined by Indigenous knowledge keepers every step of the way who could add cultural teachings to the ones based in western science? What would the learning experience out on the prairie be like then?

The problem is those kinds of teachers are few and far between and it takes time to bring them into the fold. My friends at American Prairie are doing their best and manage far more than most to incorporate these kinds of teachings and experiences into the school. I understand that the hope would be that the experiences these young people have will inspire them to be the next generation of young educators taking future students out into the field. It is a worthy goal to seek to achieve. Imagine: an entire generation of poet naturalists brimming with the songs and stories of their ancestors out sharing it all with another generation, and then another. It’s how things used to be done. I like to think they can be done that way again. It just takes time, and time too often feels like it is running out. Field School is a crucial start, and it’s good to know that the one I was part of last week isn’t the only one.

When the students left I intended to stay another day or two alone but was forced out on account of a controlled burn being initiated nearby and it seemed the area we were in was going to be something of a basecamp. So I departed3, but first headed north to the reservation town of Hays, where I had never ventured. I wanted to visit the canyon where the tribe’s powwow grounds are but the road was closed on account of flooding in the wake of a snowstorm that blasted the area the prior week. The canyon is a magical place, one I have heard many, many stories of, and I will certainly be back.

I lingered briefly in Hays, then headed back to Lewistown. On arrival I was a little early to check into my motel room so I shrugged my rucksack up onto my back and sweated out some miles. The hot shower after all that – the camping, the dust and grime, the rucking – was divine, and the cold beer I drank while sitting in my camp chair out front of my motel room watching traffic, such as it is, was maybe the best I’ve ever had.

It was a good trip and I am grateful to be invited to participate in such things.

And I am grateful to all of you who take the time to read.

With the assistance of a Paco Grande, which I swear by and, frankly, find more comfortable than any bed I’ve slept on in recent memory.

As an example of how arbitrary and bullshit blood quantum determinations are, I am significantly Nakoda (Assiniboine) from my great great grandmother, though my BQ number doesn’t say so. In addition, in the early days of writing Becoming Little Shell, it was suggested to me to see if my dad had been enrolled at Fort Belknap because there is so much overlap among people of the Northern Plains. He wasn’t. Could I be? Possibly.

But not before someone asked me, “You mean you don’t want to be hit by flaming balls from the sky?” and I replied, “I don’t want to be hit by ‘flaming balls’ from any direction!”

The paragraph starting "I loved letting other people lead the way." really struck me in a powerful way. As I age, I find myself desiring this state more. I feel like my days of being a loud and forceful voice are ending, and my days of being a quiet and thoughtful observer are more comfortable clothes to wear. I'm sure some would feel this as a loss, but I somehow feel the strength in it. Is this what maturity feels like?

Chris - Thank you for helping me see.

Damn Chris. Not sure how I'm supposed to read this and be in front of A MF KEYBOARD all day!! In all seriousness, thank you for doing this work and reporting back to us suckers stuck inside.

Also this feels like The Way: "Wouldn’t it be wonderful if the MOSS instructors were joined by Indigenous knowledge keepers every step of the way who could add cultural teachings to the ones based in western science? What would the learning experience out on the prairie be like then?"