I Want to Be Close to What I Love

And that is what the night is

Boozhoo, indinawemaaganidog! Aaniin! That is to say hello, all of my relatives! Welcome to another edition of An Irritable Métis. It has been a busy couple of weeks here and my attention has been pulled in every direction. But whose hasn’t? All the more reason to be so grateful that you continue to direct some of yours here, with me. To this I offer miigwech, which is to say: thank you.

It’s the early hours after midnight on the final sleep – the sixth – of this memorable trip. A breeze is wafting through the zipped-up mesh doorway of my tent, which is pitched on a patch of sun-baked dirt, dry grass, sage, and prickly pear cactus on a promontory overlooking the Missouri River just a couple miles south and east of Judith Landing in Central Montana. A single, small light glows from the parking area there in the distance, otherwise no human-made lights are to be seen. I usually prefer to sleep out in the open air but the evening bugs – biting flies, mosquitos, and large grasshoppers, not to mention the potential for a rattlesnake to be out seeking a warm bedmate – have made me grateful to have brought along this little single-person tent. It’s been a cozy if stuffy nest these last couple nights, when surly evening clouds threatened storms and necessitated installing the rain fly; the clouds produced only half-a-dozen or so heavy drops before drifting away.

The night is beautiful and only now beginning to get chilly. I pull my glasses out of the tent’s small interior pocket and put them on so I can see better. The stars are myriad and gorgeous and Nookomis glows waxing in the sky. She’ll be full in less than a week and if I want to see Her then it will be from my own night-darkened yard. In this moment, for the first time since I embarked with a handful of other people roughly fifty canoe miles upriver from here, I am feeling some sadness akin to loneliness. Lonely not so much for company, but for what we are about to leave behind; the settling weight of imminent return to the busy world, with busier people and busier responsibilities. It’s not the gloom of an ending vacation because this excursion has been far from that. Of all the writing adjacent work I do to cobble my living together, these workshops might be the most challenging. This one was particularly difficult. There will be a psychic and emotional toll to pay in the aftermath that will manifest as a physical one and I’ll crash for a few days. It’s just how it is.

I’m not alone out here anyway. A short distance away is a structure called the “Lewis & Clark Hut.” It is a “hut” in what I can only imagine is the view of people who consider anything less than about 2500 sq feet to be unlivable situations that must then be somehow tokenized. It’s not much smaller and is certainly nicer than what I live in. Does that make my home a lean-to? My neighborhood a camp? It reminds me that the people behind such language choices flex their supposed class and privilege so relentlessly without even recognizing it and it pisses me off, though I don’t say anything. I usually don’t say anything in such circumstances because otherwise that is all I would be talking about. I really do try to be easy to work with and get along with but sometimes, man, do I ever seethe.

Anyway, a few people have abandoned their tents to sleep on bunks in the “hut.” A couple others are also tent camping just outside it. A couple might be on the porch, I don’t know – I tend to lumber off in the evening before such arrangements are made. Then there is the rest of us, the ones who would camp a couple ridges over if we could get away with it. I am in my spot, still too close for optimal comfort but I’m managing. My relative from Rocky Boy isn’t far off, her tent tucked into a little draw between two hills, while my naturalist co-facilitator is just down the hill from me, invisible but not so far away. Any of us will only be partially mauled before help arrives if a monster comes in the night, a risk we are each willing to take. I wonder how everyone else is faring in the darkness. Are they awake and full of similar reflections as mine?

I have only been sleeping on top of my sleeping bag and now it is time to at least pull my light blanket over me so I do. I unzip the tent opening more than halfway and body up against it like I would another person in this particular hour of darkness. I want to be close to what I love and that is what the night is. I want to see the stars and feel the unhindered air and smell the deserty breeze and hear the chatter of the crickets. Finally I begin to doze so I take my glasses back off and remain that way, all but falling out of my tent, until the light of approaching dawn coaxes me back awake.

I wasn’t counting but we saw easily more than a dozen migiziwag (bald eagles), both adults and juveniles, during our days on the river. They soared in the skies overhead or, just as commonly, perched in the shade on the narrowest of outcroppings jutting from the sheer faces of the white and tan sandstone cliffs we paddled beneath. So many other birds too: doves, nighthawks, swifts, kingbirds (mostly eastern but a couple western as well), warblers, prairie falcons and osprey, just to name a few. A couple folks saw turtles but I did not. Early in the morning of the first day the canoe containing a professional naturalist AND the burly wannabe might have misidentified a riverside ranch llama as an elk but nobody is going to admit to that. Unmistakably there were also cows. Lots and lots of cows.

On the second night I was awakened from our camp at Eagle Creek by a flash of light and I wondered if there was a beacon somewhere. When I emerged from my tent to find out I was greeted by a distant magnificent spectacle of heat lightning flashing and sparking across the horizon. Huge and soundless, it was equal parts terrifying and jaw dropping. I heard coyotes in the darkness shortly after; they were audible in the night and wee hours of morning several times during our trip. Finally one revealed herself down near the beaver dam shortly after dawn the morning of our last day; moments later, as if summoned by their neighbor, a pair of amikwag (beavers) paddled out into the sluggish current while we humans were enjoying our final coffee and breakfast together.

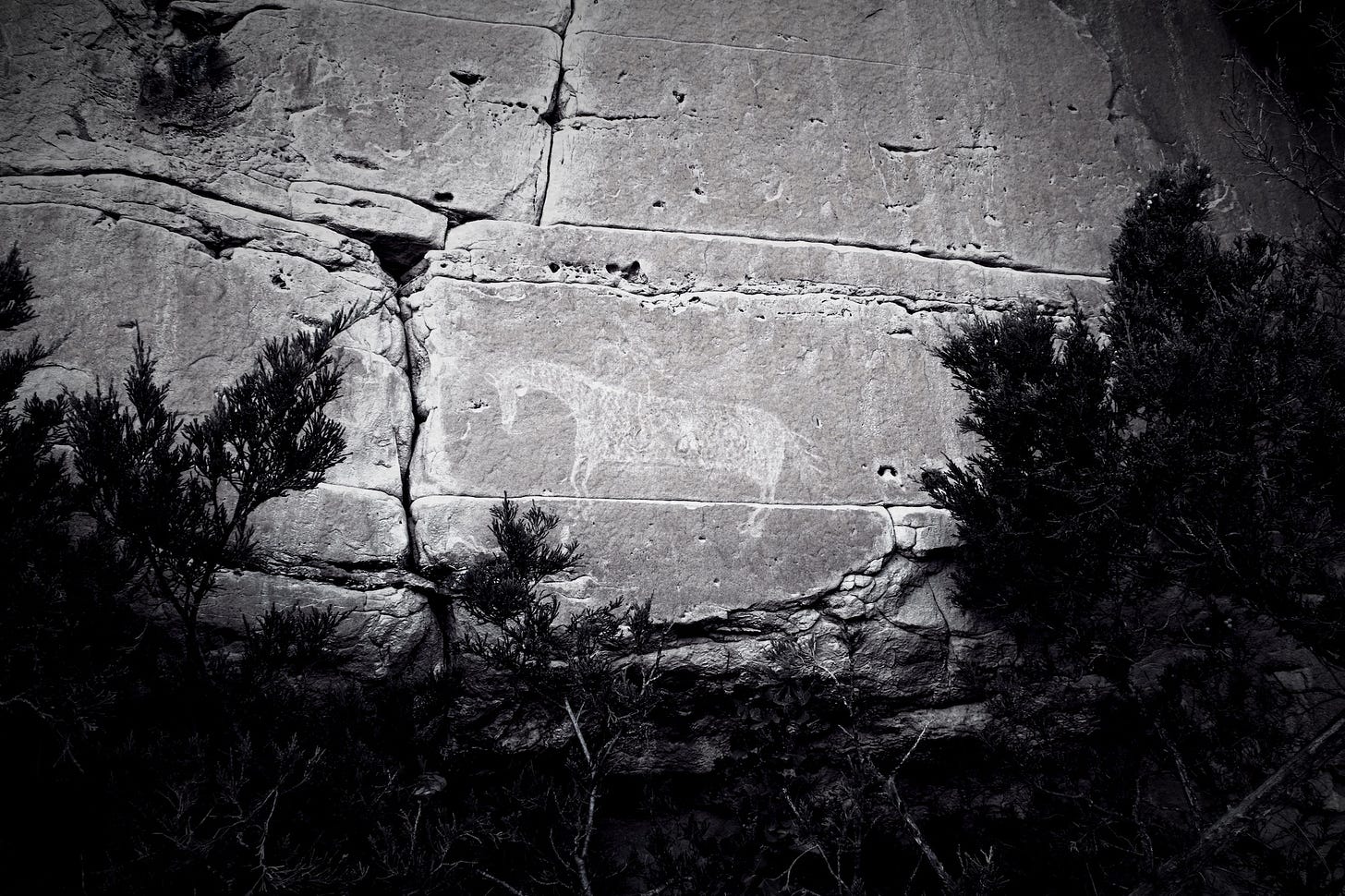

Of other mammalian relatives who used to call this place home – grizzly bears, wolves, and buffalo, especially buffalo – there was no sign. It’s like they never existed here but they did. Same, beyond some teepee rings and a couple pictographs, which I was moved to see, with my human ancestors. These people tried to live good lives, or at least lives no worse than ours. It is a measure of our modern arrogance to assume we have it so much better than anyone else ever has just because we know so little about them, isn’t it? Passing through this corridor and its accompanying rhetoric you would think it was utterly uninhabited until the Corps of Discovery passed through 220ish years ago on their military expedition. That Lewis & Clark’s effort was a military one, and that there are no remaining mentions of Indigenous people along this course now, isn’t a coincidence. That we, and our aforementioned nonhuman relatives, were hunted, driven off, and often simply eradicated from the landscape, and then erased from the discussion, was no accident. It was part of the plan all along, and the plan was executed masterfully. Lewis & Clark’s unwavering depiction as brave adventurers in a howling, undiscovered wilderness is fiction. They were in no less a known and inhabited world than if you and I decided to make the same trip today. Just because there were fewer people doesn’t mean it was less inhabited. I suggest it was more inhabited then than now, as people were far more attentive to the land every moment of every day than we are, with some exceptions, because they had to be. The Corps had obstacles to overcome, as would we today, especially as people who know what a “hut” actually is when we see one. Say what you want about the “advances” that science and “civilization” have brought to the world since but answer me this: for who? By now this summer in this hemisphere has to have convinced all but the most chowder-headed of people what our impact on the world has been, and for what? We are burning it all down for nothing more than convenience and trinkets, or “red balls” as we called them in our discussions, per an essay we read and discussed.

I feel in my bones the absence of those nonhuman relatives, plant and animal alike, that we shared the world with for millennia that are no longer in this place. It is a vast and appalling loss. It certainly wasn’t a perfect world then but I’m not on board with too much praise for much of what we’ve evolved to either.

There were surprisingly few other people out on the river, likely because of the scorching heat. When we camped at Hole in the Wall campground on night three there was a loud family group camped next to us. I did my best not to pay them attention and I hoped they would do the same for us. Who knows.

The following day the family was somewhat spread out on the river. When we stopped for lunch at Dark Butte Primitive Boatcamp, a couple canoe-loads of them came in after us. As we were leaving, a canoe with two of their shirtless young men were angling to the bank. They were hollering back and forth with someone on the shore. Apparently they’d all seen a snake and one of these two young men was bragging about how they’d gone about killing it. What a perfect metaphor. Strangers come into this land, encounter a local just trying to live a life, and slay them out of hand when sharing the landscape would have been just as easy. It made me nauseous. I was grateful to leave these people behind.

When I made the drive north from Missoula I did so without AC running in preparation for the temperature extreme we would face on the river. I did the same on my way home because I wasn’t ready yet to put it all behind me. “We suffer to prove our dedication,” I told the wonderful people who joined me for the river workshop.1 Those aren’t my words; I’m quoting Mike LaFountain, a Little Shell cultural leader whose presentation on sweat lodge protocol I attended in Great Falls at our tribal cultural center on my way up to Coal Banks. His personal history, and the stories told by a number of people in attendance who sweat with him, was harrowing. Stories of addiction, and violence, and unfathomable loss from which survival seems miraculous. The event was powerful and I’m grateful for the opportunity to have been there to witness it … but it also left me raw and rather unprepared for some of the directions our workshop would take. That is part of the suffering/dedication thing, though. You can’t talk about ancestors without expecting to open some wounds. If we dedicate to anything, we must be prepared to suffer. If we aren’t prepared to suffer, we really aren’t prepared to live.

Just outside of Missoula, when I knew my 4x75 air conditioning would stop working, I turned on the AC in my car and basked in the blast of cool air. I sighed happily. What had I been thinking, skipping this! Five minutes later the fan, without so much as a grind or groan, quit. No more AC. By the time I exited at Van Buren street, the climate I was earlier choosing to take head on was now just something making me sweaty and crabby and smellier. When the car in front of me lurched and moved timidly into the traffic circle just off the interstate I cursed loudly. I was immediately ashamed of myself for already being so disconnected from the higher place I’d been only hours before. So, as I navigated the sweltering asphalt, exhaust, traffic, and growing pall of wildfire smoke, I vowed to do my best to just be a little bit better. We are all suffering, in so many ways, all the time. Dedicated or not. We need to cut each other a little more slack.

“Ceremonies transcend the boundaries of the individual and resonate beyond the human realm. These acts of reverence are powerfully pragmatic. These are ceremonies that magnify life.”

– Robin Wall Kimmerer, from Braiding Sweetgrass

I feel like our river trip, our discussions and our dedicated suffering, was a kind of ceremony. On our final day there I had everyone take the day to themselves for reflection and writing, the goal being to then share work that evening as part of an informal reading. We all largely went our separate ways; I found my way into thick, knee-high mud that all but claimed my shoes and almost necessitated a shower and a change of clothes.2 But later, as we gathered around the tables under the covered porch of the “hut,” the unfolding evening of readings was transcendent. I was so deeply, incredibly moved by everyone’s work. There is a time in anything like this, as a facilitator, or artist, when for whatever reason you reach a point where you feel it just isn’t working the way you thought it would and you begin to despair. I certainly had those moments up until that final day, when I was proved utterly wrong.

I might not have seen the things I might have liked to see – more signs of my ancestors, human and non, for example – but I did get to see something incredibly beautiful. Something that I, and only eleven other people in the entire world, got to witness. The reading. It was something holy, and my life was magnified by it.

Miigwech, as always, for your time and attention, my friends. I deeply appreciate it. And to those of you reading this who were on the river with me, I say giga-waabamin, and hopefully soon….

No, this isn’t really suffering; I didn’t have a car with AC until I was probably in my 40s.

It did not. I achieved my goal of wearing one set of clothes the entire trip, and bathing only by immersion in the river.

Good writing and moving thoughts. I loved this: "It is a measure of our modern arrogance to assume we have it so much better than anyone else ever has just because we know so little about them, isn’t it? Thank you.

"I feel in my bones the absence of those nonhuman relatives, plant and animal alike, that we shared the world with for millennia that are no longer in this place. It is a vast and appalling loss. It certainly wasn’t a perfect world then but I’m not on board with too much praise for much of what we’ve evolved to either."

Chris,

You wreak good havoc on my heart and my mind.

Thank you.