Boozhoo! Aaniin! Welcome to another edition of An Irritable Métis. The sun continues to bludgeon us daily here in Western Montana, with highs in the 90s forecast for the foreseeable future. And yet … there is that little shift in the air, especially in the morning. The other day I was out first thing tending to this and that and I could see my breath. The grass was wet, there were little umbrella webs glittering with droplets all over the largely burned-up yard, and the light was just different than it has been. There is a bite in the air; morning is arriving a little later and the sun is making way for darkness a little earlier. The best season, Autumn – Dagwaagin in Ojibwe – is near, friends….

You know what else is near? The end of the month. Already! And unless I’m mistaken, I think I actually have fewer paid subscriptions at this moment than I did at the first of the month, though unpaid ones continue to rise. One of these days I’ll think of something of interest to make exclusive to paid subscribers to make the investment a little more worthwhile, but if you value what goes on around here regardless, it really doesn’t cost that much.

Peace on Your Journey, Mayor Engen

I want to lead with this. During the course of laboring over this newsletter, it was announced that Missoula Mayor John Engen has died of pancreatic cancer. In recent years I’ve had strong disagreement with many of his policies and how they are shaping the city I grew up in, particularly as they related to the police, homeless people, development, etc. But these are political disagreements, problems besetting every city, and Mayor Engen never seemed to me to be an unreasonable man unwilling to listen to other people. If his governance has failed, it is through the failure of those of us who have failed to organize in favor of something different. I think Engen was a decent man, an admittedly flawed man, but a man who I believe never had anything less than the best interests of our city, as he saw them, in mind. Years ago he spoke at my son’s high school graduation and while I don’t remember his words, I remember appreciating very much what he had to say to those young people. Our city can be better, but today it is worse off without John Engen at the helm. And for those of us who still want something better for our community, the task just became immeasurably more difficult.

Movement as Social Justice

Profiled in a recent issue of The Flyfish Journal (maybe the most recent one, I don’t know1) the author David James Duncan, speaking of his long-awaited novel Sun House2, tells his interviewer, “I’ve seen countless op-eds calling for a change of consciousness if humanity is to survive. I’ve seen zero op-ed descriptions of what this consciousness looks, feels, tastes, sounds and lives like from day to day. That’s the void Sun House sets out to fill, because that’s the void plaguing countless human lives.”

I think Duncan is right that these are the stories that need telling. I’m certain his sweeping epic will be a good one, even if it isn’t the first. There are any number of novels one can point to that seek to describe this upcoming world – what it looks and tastes and feels like – and, though I doubt Duncan’s is, they are pretty much all dystopian3. Does anyone really think our future is not dystopian in some fashion? That our effort isn’t so much to prevent dystopia as it is to climb out of it? Is it safe to say that there is already a majority population around the planet living a dystopian existence and the bulk of our Western-and-of-a-certain-class efforts are more about, “Oh no, we can’t let that happen to us!” There are billions of people who can tell us exactly what this life looks and tastes and feels like but no one is asking them. Maybe because their reality isn’t the one the rest of us would prefer to live in, even as we do nothing to change the lifestyles we are scrambling to maintain that are largely the cause of all this global misery in the first place … a misery which is on our collective doorstep. Which I hope is part of DJD’s point.

Friends, I’ve been reflecting more than usual lately on how the choices I make impact the world around me, rippling out into the lives of people I don’t think about often enough, let alone will ever meet. Like the people who feed me because I’ve chosen not to learn how to feed myself, for example. I’ve been thinking of them a lot this hot summer, these folks working in the scorching fields of California to harvest the crops we all depend on. They toil day in, day out, through the hottest weather, through a pandemic that left many of them sick and dead, disabled, all of it. I make a small donation every month to the United Farm Workers, but is it enough? Is it too easy to just throw money at a problem and pretend it is enough? These folks are essential in every way to our continued existence as we know it, yet how much meaningful compassion do they receive from us? Are they paid well? Are they provided adequate health care and housing? I know the answer to these questions. You know the answer to these questions. How many of us are listening to their stories, when they are told at all? Why do we get so focused on our own little dramas when the reality is that if those folks turn their backs on supporting us, we will be doomed? How do we not see the connection? There are entire industries of distraction focused on keeping our gaze elsewhere so that these inhuman systems can keep chugging along, chewing up and spitting out people largely invisible – made invisible – to us. What are we going to do about it? When are we going to do more than offer our own versions of “thoughts and prayers” to them when we are absolutely capable of doing more?

“Going back to a simpler life based on living by sufficiency rather than excess is not a step backward. Rather, returning to a simpler way allows us to regain our dignity, puts us in touch with the land, and makes us value human contact again.” — Yvon Chouinard

I like to think Chouinard is spot on in his assessment, even if he is a multi-millionaire capitalist whose life utterly lacks the majority of day-to-day challenges the greasy, toiling mass of the rest of us face. That’s the problem. It isn’t so simple. The people making these kinds of statements are never the ones juggling three jobs and raising a couple kids as a single parent. Take-out fast food isn’t just a convenient option for millions of us – when even that is available – it is the only option. Taking care of these folks is imperative too, making sure they are provided better food choices, better housing, better health care.

Has Chouinard changed his post-ridiculous-fortune life to live up to his ideals? Perhaps he has, I don’t know. It’s easy for people of privilege and means to wax philosophical over what the rest of us should do, how we should live in the world, what our emotional and spiritual approach should be. I’m reminded of Susan Cain’s latest book, Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole. I started out listening to the free audio version and was really into it, such that I ordered the physical copy because I was certain I would want to reference it again4. But then it all went largely awry for me and I'm not sure even what I initially loved about it. I can relate to sorrow and longing ... but somewhere along the way, as Cain repeatedly name drops her famous friends5, and jet sets from one expensive “retreat” to the next affordable by only the uber wealthy, I lost my ability to relate to it. She repeatedly references Sufi and Buddhist thought and practice and has probably done more to stoke my loathing for privileged white people lip-synching Eastern philosophy while living on the stolen ruins of equally profound Indigenous ways of living destroyed along the way to making the foundations of privilege for these people in the first place.

Anyway. Take a breath, La Tray. Or, as my friend Bryn might say, “Jesus, take the wheel.”

It is up to us who can do better, who can sacrifice a degree of comfort so that others can have some comfort, to do so. It is that simple. That is the change of consciousness that is necessary: give up some comfort and convenience. Who among us is really willing to do that? It’s not if, it’s when. Choose what to give up now to change directions, or be forced to give up … what, everything? Is this a reasonable philosophy?

Do you have a better one as a starting place?

Last week I took a quick dash to Minneapolis for reasons various and sundry. The weather was perfect and the adventure brought me a lot of pleasure. I also had one of the most profound experiences of my life; not unexpectedly, just beyond what I did expect. I am talking about a visit to the George Floyd Memorial at Chicago and 38th.

My first effort to talk about it was at a reading I did in Helena last weekend and I feel like my articulation of it all there was terrible. I’m still struggling to find words for it. The intersection, the painted spot where a man roughly my age, just trying to live his own struggles in a meaningful way, who, for no justifiable reason no matter what your ideas about capital punishment6 are, was murdered by an agent of the state who would have gotten away with it if not for someone on hand capture the encounter in a horrifying video, is nothing less than a holy place now. Holy in a way only possible in a place where something terrible, something earth changing, has happened. There is no other way to describe the energy there, the offerings, the spiritual gravitas that begins to settle on one while still blocks away. The immediate reflection that we have to do better for each other.

There are other places certainly, but what comes to my mind are two battlefields I have visited that have similar energy. Where what played out there is still immediate and overpowering. Both involved the Nez Perce Indians in 1877; one is to the south of me, the Big Hole Battlefield, and the other to the north and east, the Bear Paw Battlefield. Here is an excerpt from Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War, by Daniel J. Sharfstein:

In the summer of 1877, Howard commanded US forces in a small brutal war against several Nez Perce bands, including Joseph's, that had resisted moving onto a reservation. From the canyon country of north-central Idaho through the peaks and valleys of Montana and Wyoming and up to the Canadian border, Howard led a column of infantry and cavalry and sent orders to other columns of soldiers by telegraph. The people he called the "hostiles" were not simply an enemy military force. Rather, the vast majority of his foes were full families, men, women, children, and the elderly. Joseph was not a war chief; he spent most of his time among noncombatants. Through murders, massacres, and harrowing battles fought across some of the roughest and most remote terrain in the nation, Joseph's war was less a series of military tactics than a cruel lesson on what the government could do to Americans as they tried to live the lives they wanted.

That emphasis is mine. How is what Joseph and the Nez Perce were doing in trying to live meaningful lives any different from what George Floyd and his neighbors – their “full families, men, women, children, and the elderly” – and people all over the world in identical situations, are doing in simply trying to live the lives they want to live? With grifters and imperialists and racists wanting to take and take and leave them with nothing? It is the history that plays out relentlessly and endlessly. I know there are a multitude of flag waving imbeciles who think their world is the one the government is trying to do away with, but that is entirely different. They aren’t part of the solution, they are part of a problem fueled by the people best positioned to benefit from the chaos.

They too are what we are up against in remaking our world.

In an excellent piece called “Owning and Letting Go,” my friend Antonia touched on #landback. She writes:

Dina Gilio-Whitaker, author of As Long As the Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock, had a strong essay in July’s High Country News on the issues of #landback, sovereignty, and the ecological consequences of ignoring Indigenous rights and knowledge for centuries:

Land return does not mean that everyone who is not Indigenous to what is today called the United States is expected to pack up and go back to their ancestral places on other continents. It does mean that American Indian people regain control and jurisdiction over lands they have successfully stewarded for millennia. This includes the return of public lands.

The more I read about these histories and issues, and the more time I spend in the lands around my home, lands I love and feel attached to in ways I can’t fully express, the more I think about what it means not just for people to be torn from their land, but for the land to lose its people.

I urge you to read and subscribe to her newsletter. Nia is way smarter and more knowledgeable on land, the commons, etc. than I am and I have learned so much from her.

I’m big into #landback. I talk about it all the time. One of my favorite shirts says LAND BACK as rendered into the Black Flag logo. But I’m troubled by all the rhetoric around it, even in the otherwise excellent article that Dina Gilio-Whitaker wrote that Nia references, for a couple reasons.

First, I think, like land acknowledgements, there is a segment of settler bureaucracy that is co-opting it as a means to score clout without doing anything. I’m reminded of a woman who attended a presentation I did in Choteau last month with Métis elder Al Wiseman. From the “more comment than question” gallery she went on about how she’d attended an event in Yellowstone where some uniformed bureaucrat went on about managing the land like Indigenous people did, or some shit like that. A great idea in theory, but what does that look like in the real world, and what is this guy going to do to facilitiate it? Probably nothing. But it sounds good in a speech.

The second problem I have is the stereotyping of Indians that this rhetoric also presents, that somehow we as Indians have innate connection to the world and can somehow save if if we just “go back to how it used to be.” Well, what does that world look like? I’m sure my Plains Chippewa ancestors did a great job of managing their environment as needed. Same as the Cree and the Blackfeet and the Cheyenne and the Dakota and everyone else. but that was entirely a different world. The plains are no longer covered in native grasses. The animals that were relatives in this management are no longer there. It is a completely different landscape. That, and now most tribal governments operate in a fashion dictated and modeled on colonial governments. Our relatives up north of the Medicine Line often find themselves fighting their own tribal governments in opposing pipelines.

You can always find Indians happy to agree with whatever colonial powers want them to. That is as big an issue as the idiots waving Gadsden flags, most people just don’t know about it.

Giving the land back to Indians wherever possible is essential. But we aren’t going to magically save the world; we have to relearn a lot of how things used to be. This too will require a collective effort across every demographic imaginable, everyone doing their part. A movement worldwide unlike anything we’ve really seen before.

As a writer I spend a lot of time on my ass in a chair, even as I’ve defined my writerly aspirations akin to this quote from Mark Jenkins, a writer/adventurer who years ago kept a regular column at Outside magazine called “The Hard Way”:

“I cannot get enough of the world. To smell it, walk through it, sink the teeth of my mind into it. I am not a writer who began writing at the age of eight in a little room at a little desk and dreamed of being a novelist. At eight I was flying on a bicycle through the pungent sagebrush in the red hills beyond the edge of town.”

As I get older, I don’t bounce back as quickly from hours in the chair as I used to. If I don’t keep up my hiking practice my body is eager to remind me I haven’t. If I don’t remain mindful of moving, of movement, I suffer for it.

I’ve been reading off and on the work of writer and biomechanist Katy Bowman. Her collection called Movement Matters: Essays on Movement Science, Movement Ecology, and the Nature of Movement, begins with this statement:

That movement matters isn't earth-shattering news. It's pretty basic physiology, actually. But just as basic, although it takes a bit of explanation to get there, is that our lack of movement doesn't only affect our bodies negatively; it also negatively impacts the planet we live on. I once heard humanitarian Ashley Judd say that it was abusive to point out a problem without offering a solution, and so as much as I feel this problem needs to be extremely well defined and thoroughly explained, alongside I'd like to suggest, at least in part, a solution: you need to move more than you do right now. You not only need to move more, you must also move better. You not only need to move more and better, you must also move with other people, and move through, around, and over some natural terrain. If you can't convince your tribe to move more, you must create a new tribe. Which often requires (ironically) that you move. Move at your job, or move jobs, move homes, or at least move furniture around or out of your home. Your contribution toward a solution to many problems, whether they're related to illness or finances or loneliness or boredom or feeding the underfed or freeing the oppressed, can often be “move more.” Small and large issues alike can feel overwhelming, but often this is a result of trying to solve problems without changing anything about the life that created them. And so, allow me to show you how to move, for a better body, a better life, and a better world.

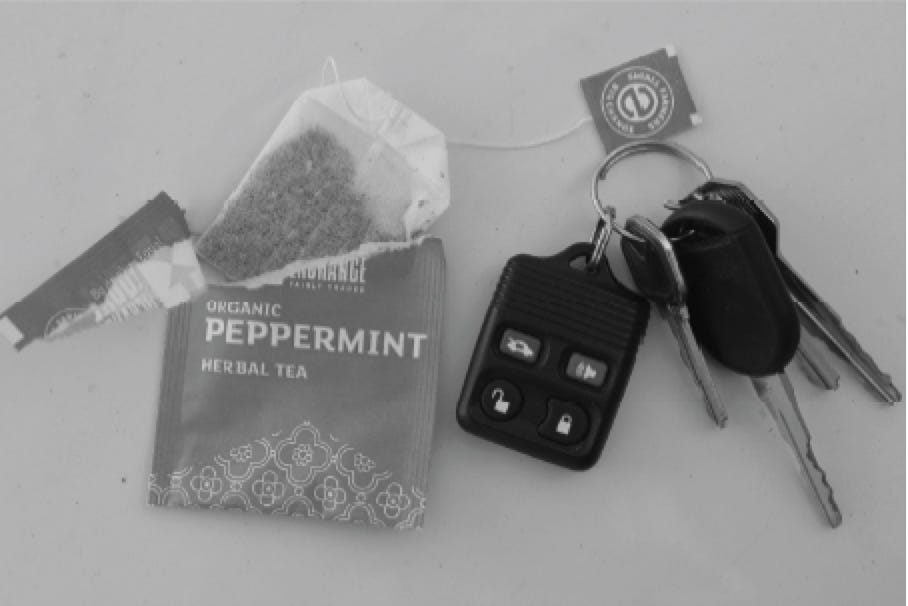

I love this take on getting off our asses. Not just for our personal, seized-up, stove-in, heaved-to physical well beings, but for our wider community. I think about it all the time, my personal failings and sedentary proclivities not just as a bitter, aging old man, but as someone trying to, if not offer answers, at least raise questions in hopes that we might collectively find answers to them. I was thinking of this next passage last night while dumping beans into my coffee grinder, then pressing the button to churn them into powder, then getting it all together just so it would be ready and waiting for me the next morning. The passage is from a chapter called “Movement Outsourced” and includes this image:

These items – an electronic car unlocker and a tea bag – are convenient. But what I've realized is, when we say or think “convenience,” it's not as much about saving time as it is about reducing movement. We can grasp sedentary behavior as it relates to exercise because it's easy to see the difference between exercising one hour a day and not exercising one hour a day. My work, in the past, has been about challenging people to also be able to see the difference between exercising one hour a day and not exercising the other twenty-three. More subtle still and what I'm asking you to do now is to see how the choice to move is presented to you every moment of the day, but how most often we select the most sedentary choice without even realizing it.

Our daily life is composed of a lot of seemingly innocuous ways we've outsourced our body's work. One of the reasons I've begun focusing just as much on non-exercisey movements as I do on exercise-type movements is that I feel that the ten thousand outsourcings a day during the 23/24ths of your time hold the most potential for radical change. Be on the lookout for these things. To avoid the movements necessary to walk around to all the car doors, or just to avoid turning your wrist, or to avoid gathering your tea strainer and dumping the leaves and cleaning the strainer (in your dishwasher?), you have accepted a handful of garbage, plastic (future landfill), and a battery. To avoid the simplest movements, you have – without realizing it – required other humans somewhere else in the world to labor endlessly, destroy ecosystems, and wage war … for your convenience. Sedentarism is very much linked to consumerism, materialism, colonialism, and the destruction of the planet. If you're not moving, someone else is moving for you, either directly, or indirectly by making STUFF to make not moving easier on you. You were born into a sedentary culture, so 99.9 percent of your sedentary behaviors are flying under your radar. Start paying attention. What do you see?

Physical movement as social justice. The head wants to explode.

Are you paying attention?

I want to know what you see in your world.

On several occasions I have taken the opportunity to tell a version of the Anishinaabe creation story that explains why we call North America Turtle Island. I specifically like to share the story with children, but I’ve shared it with adults too. The point being, after a flood has drowned the world, all the surviving animals – along with Waynaboozhoo, or First Man – realize they need soil from the bottom of the lake to re-create the world. Waynaboozhoo dives and fails. Mahng, the loon, a great diver, tries and fails. Mink, otter, even turtle, all try. All fail. Hope seems lost. Then one of the most insignificant among them, Wazhashk, muskrat, offers to try. He is laughed at, even jeered it. But he tries anyway … and succeeds, though he loses his life in the effort. The handful of soil he brings up from the bottom is placed on Mishiikenh’s, turtle’s, back, and from there the land is renewed. And here we are.

I tell this story for a couple reasons. It is more important that children know that what they do matters. It always matters. That exceeds any notion of, “You can be whatever you want to be!” because we know that is largely bullshit. But to know what you do matters, that your choices matter, that is important. That to be small isn’t to be insignificant.

It is important for us to remember that as adults too, isn’t it? Our choices matter in ways we can’t imagine. But so do our efforts, no matter how small. How insignificant. Our movement matters. Let us not succumb then to despair amidst these rising waters. To get through this, to make sure everyone emerges from the deluge, will require many different tastes and feels and sounds in the new world. We just need to do our very best to take up and deliver our own tiny contributions to seeing that the future unfolds in a good way. Our ancestors have done this time and again. We can do this. We must do this.

Miigwech for hanging with me on this long one, friends. I’ve had a lot on my mind. Know that I wish for nothing less than mino-bimaadiziwin for all of you. This is the Ojibwe idea of living a good life. A holy life. A beautiful life. We choose this life; every footstep a choice, every footstep a prayer.

I gave up fly fishing and fly fishing magazines about four years ago. The profile (it’s a good one) uses a couple photos I took of Duncan so they sent me a contributor copy. The check that represents compensation for the use of those photos, however, remains … elusive.

Due around this time next year or so

My hands-down favorite is Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waub Rice. Just trust me on this.

Anybody want my copy? I’ll happily mail you the friggin’ thing….

One of her “heroes” in the story is a venture capitalist who whines about not being appreciated for making the Ten Most Odious Professions on the Planet list or some shit. Is there ANYTHING more exemplative of American “Burn it all Up!” capitalism than a venture capitalist?! *pukes*

Let me help: there is no justifiable reason for capital punishment

I’m AKA sofasaurus because I revel in a sedentary lifestyle, so I relate. The one thing I still do which takes a lot longer is to hand water my outdoor container garden. It creates more movement (refilling my watering can), but I talk to each plant, feel the soil around them, pick the stray weeds and dead leaves, and generally access the health of my plants. Very rewarding too, when I see each day what I can harvest. Thanks for your always encouragement to make us better humans and better stewards of our tiny domains.

We are retiring after 30+ years in public education and moving from north central Idaho to Lummi Island in the San Juans next spring, ruthlessly downsizing, shedding off dishes and glassware and heirlooms and furniture and a family piano and excess clothing and cookware and many many books. I feel so torn because people like me are needed in Idaho to fight the extremists, the "patriots," the religious who feel compelled to force their tenets on their neighbors, those who want to destroy public education, those who are cheering the most restrictive abortion laws in the US, those who believe that the Nez Perce and others should just somehow get over the looming end of the salmon runs. But I'm tired and disabled. I am selfishly choosing to withdraw to a place with nature reserves and trails, herons and eagles, tides and a CSA, reef fishing for salmon, a community darts league. I know very well that we are privileged to be able to do so, I recognize the hideous suffering of others all over the world and here and yet, I am selfish, I am so weary, so very weary, and the end of my life is far more real than it used to be. I am also bitter, Chris, and resent rednecks and what gazillionaires are doing to our politics and our planet, and avoid Ted Talks like the plague. Thank you for building this community. It is a solace.