Boozhoo, indinawemaaganidog! Aaniin! That is to say hello, all of my relatives! Welcome to another edition of An Irritable Métis. Occasionally I get messages from folks inquiring about the Ojibwe words I often sprinkle here and there throughout my newsletters. Email too, for that matter. I only know a few words, and even fewer phrases, and I use them as I learn them because I want to. I lived half-a-century before they started arriving again in my consciousness and I’m not going to waste any more time seeding them back out into the world. They are beautiful, and it seems people appreciate seeing them, if not necessarily understanding how they might sound. Ojibwe was never meant to be a written language, so if you sound the words out phonetically you’re going to be pretty close because that is exactly how they are written down: phonetically. There are no unfamiliar symbols to represent specific throat and tongue sounds like you might see in Salish or Crow either, which makes it a little easier. But it still isn’t easy, especially since I am never around people who speak it. A great resource for this language and what it sounds like is an Ojibwe man (of Turtle Mountain descent, just like me!) named James Vukelich Kaagegaabaw. He has videos on both YouTube and Instagram and they are wonderful. For example, if you want to hear exactly what my greeting for every newsletter sounds like, and its broader meaning, you may dig that HERE.

I look to James and the work he is doing almost every day. Same with the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary. And a handful of books I’ve gathered, both reference books and books by people doing what I am doing: using words as they are able to. Keep in mind there are regional differences with words and ideas, different spellings, different takes on stories, etc. and that complicates things further. Ojibwe people are Anishinaabe people, and we live all over the place. Certainly I get as much wrong as I get right; I was about to say I am the last person you should turn to for knowledge on this language but that isn’t necessarily true either. I am well aware I am incredibly ignorant and yet I do know a few good places to find answers and I am happy to share them. For me to keep mum and not share this stuff that is readily available anyway would make me the worst kind of gatekeeper and that is the last thing I want to be. How could I claim to believe that we are all Anishinaabe – and I do! – and then turn around and try and hoard knowledge and teachings that have been generously bestowed on me from other people? So I will not. There is little that breaks my heart more than what has been done by this common North American settler culture in its ongoing effort to stomp out the human languages of this Place. Every word spoken in a Native tongue on this continent, on this Turtle Island, is a life affirming act of defiance. Every single time.

Finally, remember that when you pay for a subscription to An Irritable Métis you aren’t just supporting me and my work. Your support makes me able to do what I do, yes, but it also enables me to support other people fighting the good fight via my own donations and subscriptions. We are all in this together, my relatives, and support here is support for many, many other writers, thinkers, activists and artists too. Miigwech!

Most days I’m up early. I don’t use an alarm and I’m always a little shocked and dismayed if I crawl out of my nest after 7:00; this time of year the sweet spot is around 5:30, 5:00 during the sunnier months. Sometimes I linger until a little after 6:00 even if I’m suitably awake; I tell myself it’s okay because 6:00 is when the coffee maker kicks on, and who wants to rise before the coffee? Still, I’m most productive early, when I’m productive1 at all, and I like the fresh energy of the world as it emerges into a new day. I usually sit at my window on a cushion and burn some sage – a practice originally born as a Zen thing with incense but ultimately redefined and Indigenized a bit by my readings of Richard Wagamese – then wander out onto the back porch to see what is to be seen in the sky. Today for example Nookomis, the Ojibwe word for Grandmother, who is also our beautiful Moon, was high in the sky, Her light burning through a thick mist. A nimbus glowed around Her; it was a moonbow, circling Her in the colors of the rainbow. I like to think of it as Her ribbon skirt, and the rainbow hues are a celestial display of Pride colors. Because of course She would wear one, wouldn’t She? A ribbon skirt for Pride? Colors for all people, all identities, all viewpoints? Nookomis loves all of us, without condition. It is an important teaching.

From the porch I also listen to what the new morning world sounds like. There is distant traffic on the interstate some miles away, and usually some closer still on nearby Mullan Road. The occasional neighbor leaving early; this season it is the sound of tires crunching through frozen slush that I particularly love. Dogs bark. I’ve heard ducks whistle by overhead, and honking geese. Summer roosters crow and cattle low and the occasional donkey brays. I love every little bit of all of it. It is this slow unfolding, this early lingering, that is possibly most important to the success of the entire day. I’ve worked hard to create a life where the least number of “have tos” occur first thing and I do my best to protect this. My mornings are a kind of ritual, and an important one.

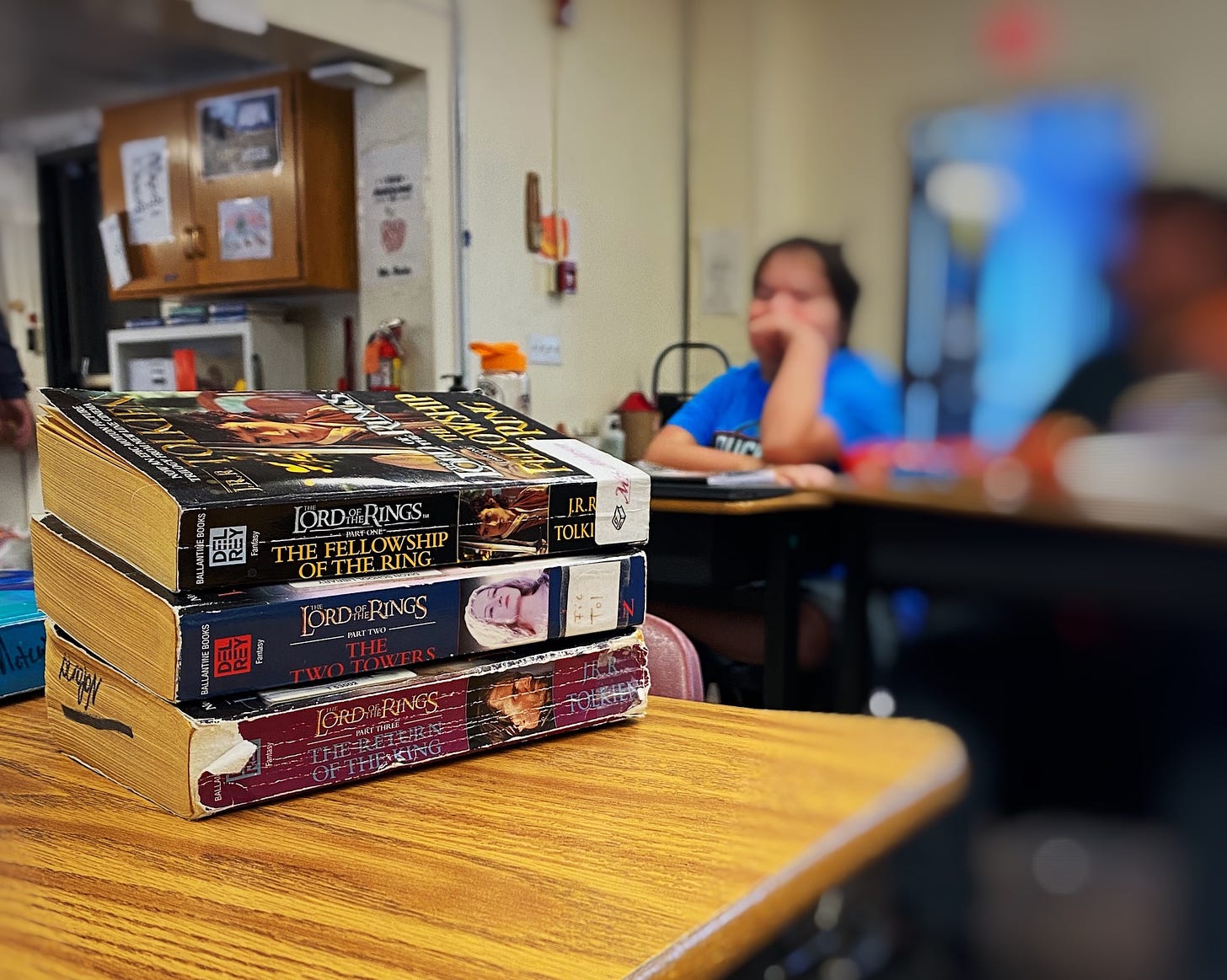

I did set an alarm for both last Wednesday and Thursday, though. I’m happy to report that on both days I woke and turned it off before it sounded2. The reason for setting it in the first place is that my teaching responsibilities up north – new subscribers here may not know that for the last couple years I have taught poetry to elementary school kids on the Confederated Salish & Kootenai Reservation as 12-week residencies on behalf of the Missoula Writing Collaborative – resumed with the arrival of the new year. I’ll be in both places every week through March. It’s an hour drive on Wednesday to be in Ronan by 8:30, and nearly as long to get to Dixon on Thursday almost as early. So I couldn’t risk being shiftless and late. In Ronan I teach four classes, all 4th graders. In Dixon, a much smaller school, I teach three classes that combine students from 3rd-through-8th grade. It’s challenging in both places for different reasons.

Wednesday I got up and turned the coffee on before it started on its own. Then I headed straight to the shower. By the time I finished there the coffee was ready. I walked out into the kitchen, turned on the stove light so I could pour a cup, then shut it off and shuffled down the hallway. Nookomis was out and near full that morning too, and light from around the drawn shades in the living room was enough to navigate by.

I walked into the darkness of my office with my coffee in my hand. Before I even flicked on the desk lamp I heard it: the hoot of an owl, followed shortly by another, slightly higher-pitched. The conversation between female and male great horned owls, and they were close. As in, sounds-like-they-are-in-my-room close. It’s not unusual to hear them but they are rarely this near! I set my coffee on my desk and crept to the window and slowly pushed the curtains aside. There are several trees across the road from me, and I suspected the male was in the Ponderosa pine opposite, and the female in an adjacent cottonwood. It was too dark to see them but they kept up the conversation. I was elated. I sat down in my chair, kept the light off, and decided not to do anything else as long as they were there, up until I had to get ready to leave. I also reflected on why they might be visiting me. Why so close, and why today? Were they talking to each other, or were they talking … to me?

The Ojibwe word for owl is gookooko'oo. Among the many ways that Anishinaabe culture relates to owls, we believe they help souls who have died find their way safely to the spirit world. They are also capable of delivering messages from the spirit world back to those of us still living. Were they here to tell me something, to remind me of something? What message might they be delivering?

I thought about the answer, and took the question with me to the 4th graders in Ronan, and then to the classes in Dixon on Thursday. Not every class (plans often get derailed right out of the gate and I tend to go wherever the students take me!), but at least three or four of them. I talked about the owls, the message they might be sending, and from whom. It is magic to see the thoughts and emotions play out on all those young faces as they consider my occasionally odd questions.

Here’s what I think. I believe that those two gookooko'oog were indeed delivering me a message. Not just from my ancestors, as the children mostly suggested, but from theirs as well. Reminding me to be good to them, to teach them well, and to be patient in knowing that the way we choose to teach children in this culture isn’t necessarily the best way to do it, especially these children. The ancestors wanted to remind me of the importance of our time together. How truly critical this opportunity to share our lives and our stories is to all of us involved; to the kids, how that will affect their families … to the teachers and their lives … and what it will mean to me and mine too. Everything we do is connected, isn’t it? Everything we do can be a learning experience if we listen, if we really pay attention, to each other.

Sometimes an owl is “just” an owl, but I was thinking of them in the bigger picture, as concerned relatives, on that auspicious morning preparing to return to the reservation and its children. After all, future generations of Human People will certainly have something to say about the lives of future generations of Owl People; on future generations of all People. Telling this story of the owls allowed me to underscore my efforts to urge these students to pay close attention. Not just to the physical world, but to the one beyond our conscious senses. From how our ancestors speak to us, and how we influence the people we will be ancestors to. So much is happening, all the time. We don’t want to miss any of it if we can help it!

Gookooko'oo plays an important role in guaranteeing Anishinaabe mino-bimaadiziwin, which is the good life. Where every footstep is a prayer. It’s funny because I was thinking that earlier, before I heard the owls, of reminding the kids that in living poetry, every footstep becomes a poem. That I would make sure and deliver that message, the one I consider most important, right out of the gate. And these gookooko'oog showed up to remind me of the deeper nature of our interactions as well. Everything connected. I am moved by it all. Chi-miigwech, Gookooko’oo.

I will talk more about the interactions with the students over the coming weeks, I’m sure. I wanted to start here, though. I wanted to make sure anyone reading this who might need to think about what the gookooko'oog had to say have a chance to hear it. This is another example of a teaching too that came to me and I feel obligated to share with others as well. I’m not around elders and I don’t sit at the knee of a wise mentor or guru, not by any means. Is it arrogant of me to think I am being taught what I need to know largely by books and my non-human relatives? Possibly. Probably. No one is forcing you to listen to me, though, and you certainly don’t have to. Like anyone else, I am just making my best effort at living in mino-bimaadiziwin, and this is what my good life looks like….

Just Dropped

I’m doing a couple things with Freeflow this year, and the first one – a virtual workshop over four Tuesdays in April – has just been announced. You may check it out HERE! This is what it’s about:

“Despite our great fortune to live in a time when we aren’t at great risk for communicable diseases, we are, in fact, dying – slowly, in bits – from our natural tendency to do as little as possible. Our unquenchable desire to be comfortable has debilitated us. Ironic, as there is nothing comfortable about being debilitated.”

— Katy Bowman, Move Your DNA

From Chris:

Too much of our writing is dying too, friends, the same death and debilitation of convenience and attention-theft that our bodies are. Glossy and clean and neat around the edges when it should be muddy and a little smelly and bleeding from being dragged through the brambles. Just like our bodies after a vigorous trip out and back! It is never too late to pull ourselves back from the brink, then, and that is what this workshop will attempt to do. In the same way we think of movement as a kind of rewilding, we will attempt that on the page.

Over four weeks we will discuss what it means to “rewild” our writing – how to influence it through movement and how to be inspired by movement. Physical movement in the physical world, but also metaphorical movement in the wilds of our brains, where we push into weedy patches and the rough terrain we tend to avoid out of convenience, and for fear of the unknown.

I hope some of you will consider participating! Scholarships are available, I think. Just contact Freeflow if you think you might be interested in something like that. It will be upon us sooner than we all might think!

Chi-miigwech for sticking with me, my relatives. I hope you are all doing well!

Writing this awful word, “productive”, I’m reminded how much I’ve come to loathe it, that it is representative – along with other words like “professional” and “landlord” and “should” and “unpack” – of a life and culture I want no part of. Begone, awful word(s)!

Alarms are a hell of a way to be jolted from sleep in any context, aren’t they?

I wonder what could shift in our lives--not just our own, but everyone’s--if we started every day with even the smallest ceremonies and the smallest noticings, and kept doing it. Especially if the rituals include an acknowledgment of gratitude, even a tiny one.

There are two owls living in my in-town neighborhood where old sycamore and fir trees surround older homes. Sometimes they talk for hours into the dark night. A pair of hawks nest in the tallest tree on our block and I look for them sailing back and forth to the sluggish Snake River to fish or find a vole or other tiny mammals. In the summer, osprey nest nearby and I get to watch the chicks fledge with parents screeching, reeling above and around them. Watching, listening to the birds nudges me forward toward a conversation with these creatures, an invitation to listen more closely to what wisdom they have to share.