Boozhoo, indinawemaaganidog! Aaniin! That is to say hello, all of my relatives! Welcome to another edition of An Irritable Métis. This is quite possibly – even likely! – the final edition for 2022. I am grateful to have you here reading this newsletter. I am grateful for the interactions, the collective irritability1, and everything else that has happened because of your support. It means everything to me! However, this isn’t some kind of year-end retrospective; I may do that in January, I may not. The only thing of note about this edition is that it is probably the last one I’ll file before the celestial odometer rolls over again. Which means the next post after this one will be another edition of the “A Few More Sentences” series for paid-subscribers only. After that there won’t be another paid-only post until February, I promise. In the meantime, it’s not too late to get your own paid subscription here before the year gasps its last!

Something notable for my Missoula-area subscribers: This is a bit last minute (because I sort of forgot to mention it and all of a sudden it’s upon us) but I am doing a live event this Wednesday, December 28th, from 7:30PM – 9:30PM at the Roxy Annex on the Hip Strip in Missoula. All the details are HERE. It is an intimate setting with limited seating, so if you think you’re interested don’t wait to buy tickets. At that link, click the 7:30PM button to buy if you are so inclined. This event is part of a series called “Writers in the Round” and I’ll be with two good friends: singer/songwriters Travis Yost and Christy Hays. It’s going to be great!

The other night I received a wonderful email from a writer friend2 who was messaging me, as he described, “on Christmas Eve, from a bar with a ceiling dangled with cowboy boots in my wife’s hometown in California.” He was writing, among other things, to tell me how moved he was after reading James Welch’s The Death of Jim Loney, which I had mentioned some months back on this very website, and to thank me for mentioning it. I was moved by the note, and that he would reach out to say so.

I loved our exchange. I love how art connects people. I’ve spoken many times of how, after OSJ came out and started picking up steam, my exploration of haiku poetry unexpectedly opened a connection across time and space and culture to Japanese and Chinese poets writing along the same themes as I do, but hundreds and thousands of years before me. That cosmic exploration and influence manifested in my second book, Descended from a Travel-worn Satchel. This work, and my relationship with fellow writers and the enthusiams shared with other people who love similar things, are the basis for many of my friendships. Most of them, in fact. It is a magical thing, this exchange of passion for creative work and creative people, and it is something worth getting out of bed for. Isn’t that what brings us all together here?

“I've worn out my body in journeys that are as aimless as the winds and clouds, and expended my feelings on flowers and birds. But somehow I've been able to make a living this way, and so in the end, unskilled and talentless as I am, I give myself wholly to this one concern, poetry.”

— Matsuo Bashō, writing in a letter to a friend.

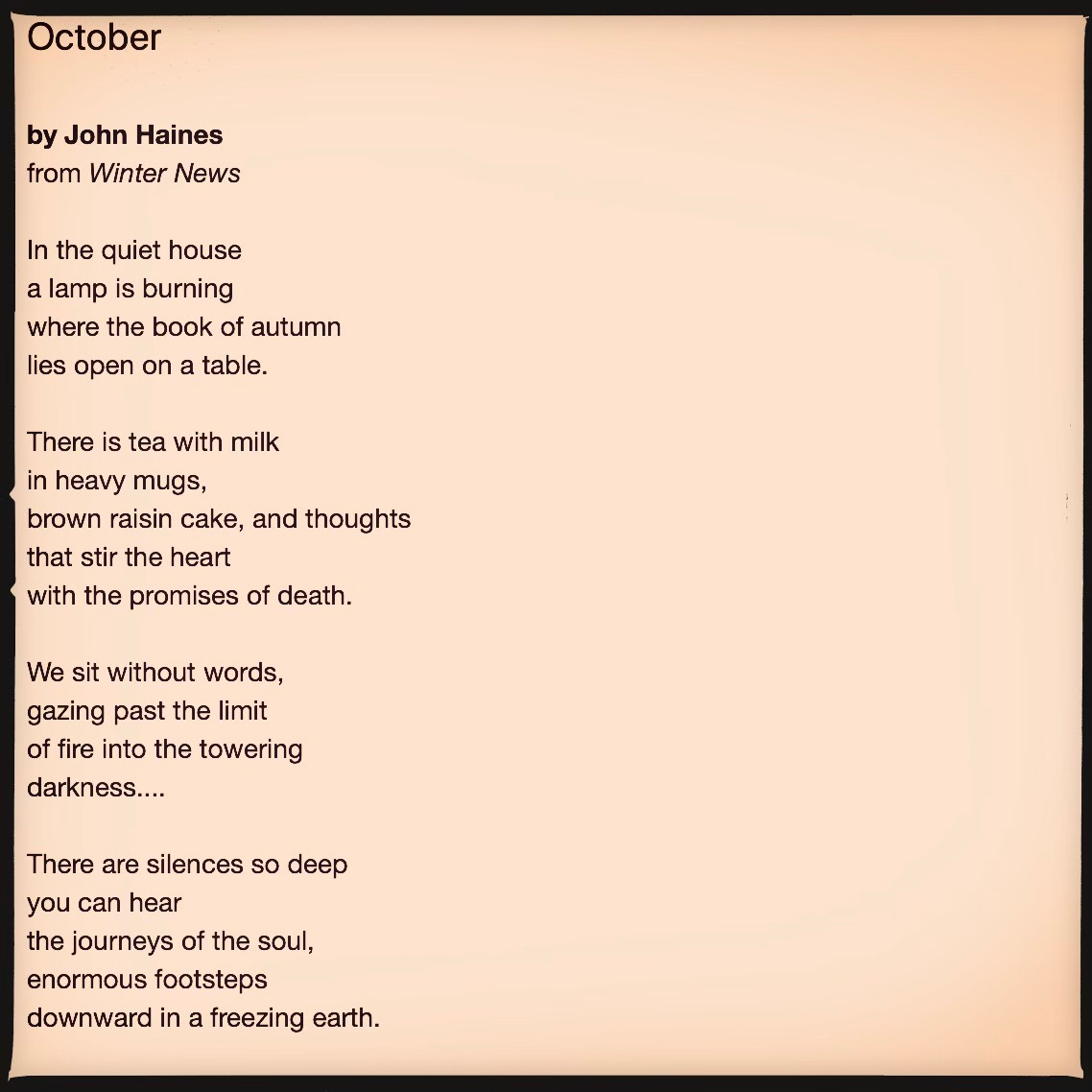

I've been thinking of all this a lot lately, having recently finished John Haines's memoir of Alaska, The Stars, the Snow, the Fire: Twenty-Five Years in the Alaska Wilderness. I came to this Haines book in a roundabout way that buttresses my celebration for the sharing of art. In an interview with Barry Lopez he mentions the American contemporary composer John Luther Adams3. I think Adams surfaces also in at least one of Lopez’s books; if not Arctic Dreams, then certainly Horizon. As a result of that mention I sought out Adams’s music, and it has been a staple of my writing soundtrack ever since. In 2020 Adams published a memoir called Silences So Deep: Music, Solitude, Alaska, about his forty years living in Alaska and I loved it. In the book he describes his close relationship with the poet John Haines. I found a used copy of Haines’s 1966 book of poetry called Winter News somewhere. Amazingly, my copy is signed by Haines. Adams is so influenced by Haines that the title of his memoir is taken from a line in the poem “October” from Winter News. Connection after connection after connection.

It gets deeper. I keep a list of books I read on Goodreads. I don’t interact on that website, I just like to see the books I read all gathered in a list with pretty pictures of their covers. When I added The Stars, the Snow, the Fire to my list, the website displayed at the top of the entry a review written by my friend Ron Scheer, dated April 18, 2012. It made me smile. Ron and I shared many literary interests. He was a good friend, though I met him in person only one time when he came to Missoula for a Western Writers Festival of some kind that happened to be in town the same weekend as the 2011 Montana Festival of the Book. Ron was incredibly smart, kind, and erudite. He was also a voracious reader and writer.

Ron tragically died of cancer shortly after retirement only three years after writing his review of the Haines book. He was a magnificent man. Another friend of mine, David Cranmer – the first guy to ever publish my fiction, a crime story called “The Pickle” – was also an acquaintance of Ron’s. He wrote this beautiful remembrance of our mutual friend on Ron’s blog, “Buddies in the Saddle.” If you want to read a brief story of a wonderful man, I urge you to check out “The Cowboy Rides Away.”

It’s no surprise that Ron would reach across time and space to share with me his enthusiasm about a book. His review of The Stars, the Snow, the Fire is better than anything I could say about it, so I share it here in its entirety for your enjoyment as well:

“I came across John Haines while reading William Kittredge's great anthology "The Portable Western Reader." Haines is better known as a poet, and maybe that's why these essays are so vividly written. They represent a period of years from the 1940s to the 1980s during which Haines homesteaded off and on near Richardson, in central Alaska. They are only somewhat reflective and focus instead on capturing the raw experience of living in the woods, along creeks and rivers, through the seasons of the year. As a homesteader, Haines lived off the land, raising his own vegetables, hunting game, and trapping marten, lynx, beaver, and fox. Many of the essays concern hunting and killing animals, and they are written in a matter-of-fact way that may repel some readers. They do, however, capture a point of view toward wildlife that is possible for a man of letters to entertain, and as such they illuminate a set of values that has a long history among people who have lived by hunting and gathering on the frontiers of the world.

For me, the memorable essays in the collection deal with the kind of isolation that the author has chosen to live in. One essay describes a three-day winter journey to check trap lines, cataloguing in detail how he dresses, the gear and food he takes with him, and the one dog that accompanies him. Along the way, he has a close encounter with a grizzly, which highlights the vulnerability of a single man in this remote terrain, and there is the description of overnighting in a cabin, where he is alone with his thoughts as darkness falls early, silence reins, and the cold night sky fills with stars. Another essay is a long account of how the streams and a nearby river gradually freeze over in the autumn and winter. With his poet's eyes and ears, Haines describes how ice forms and the sounds made by flowing water as it freezes, until it is utterly silent under snow.

A few essays describe the men who live in this area, swapping stories about others who have chosen this faraway world to live in alone and make what living they can to keep soul and body together, season after season. Given these lives of isolation, the prevalence of dark and cold, and the recurring theme of death and dying, there is a certain melancholy throughout the book. You put it down at the end with a kind of respect for Haines' clear-eyed vision and sensibilities and certainly his skill as a writer. The simplicity of a life stripped to essentials (work, food, sleep) will have an appeal for some readers who dream of self-sufficiency and getting away from it all. But the romanticism Haines evokes has much to do with a test of character, spirit, and physical stamina. The tough and the lucky survive, but only for as long as the wilderness lets them.”— Ron Scheer, April 18, 2012

Ah yes, Ron, the “certain melancholy” that lives in this book. That melancholy is a large part of what speaks to me as it relentlessly lives in my mind while I muddle through edits of my book, which at times is more emotionally heavy for me than I ever really wanted it to be. This time of year, much as I love it, also makes me sad, and the darkness of the season amplifies all this emotion and the proximity of the events I write about is ever present. Recently, sitting in the same chair I am now, I decided to walk out into the dark and see the moon and stars because they were as bright and as close as they ever get to what they were like back at my folks’ place 30 years ago. In a frayed old Carhartt button-down and yoga shorts about a size-and-a-half too big, I threw on a hoodie and a vest and some sneakers and went out. About a quarter mile out I realized I might have been just a tad under-dressed but I lived, and the discomfort contributed to my joy in being outside.

Still, that night out was nothing like this stretch of weather we’ve endured recently, over the Solstice and into Christmas, where a walk like that could mean I might not return. Temperatures plunged well below 0° Fahrenheit, with windchills driving it even colder. I made time to revel in the cold, letting it burn my face and try and get in under the heavy Carhartt coat that I inherited when my father died. That is its own visitation, his spirit with me in such conditions in the form of this coat, that feeds both love unbound by presence and the lingering melancholy from the lack thereof.

The first night was a little ominous, wondering what would happen. The next morning the house creaked and cracked in ways I’ve not heard it do before but everything held up. No emergencies here, no frozen pipes like we often endured when I was growing up. Cold nights where my sisters and I got up and huddled around a little electric heater; cold nights when the water in my oldest sister’s goldfish tank turned to slush. My house was warm and my shower was hot and I was almost embarrassingly grateful for both the challenge of cold and my ability to hide from it.

There is a danger in these extremes most of us don’t often have to face. Haines writes about it in The Stars, the Snow, the Fire in this passage I highlighted, speaking of those solitary men Ron Scheer also took note of, and the ones who simply disappear.

A drowsy, half-wakeful menace waits for us in the quietness of this world. I have felt it near me while kneeling in the snow, minding a trap on a ridge many miles from home. There, in the cold that gripped my face, in the low, blue light failing around me, and the short day ending, in those familiar and friendly shadows, I was suddenly aware of something that did not care if I lived. Or, as it may be, running the river ice in midwinter: under the sled runners a sudden cracking and buckling that scared the dogs and sent my heart racing. How swiftly the solid bottom of one's life can go.

Disappearances, apparitions; few clues, or none at all. Mostly it isn't murder, a punishable crime- the people just vanish. They go away, in sorrow, in pain, in mute astonishment, as of something decided forever. But sometimes you can't be sure, and a thing will happen that remains so unresolved, so strange, that someone will think of it years later; and he will sit there in the dusk and silence, staring out the window at another world.

As of two days ago, at least 55 people have died because of this storm. Certainly there are many, many more. Some may never be discovered. People disappear all the time, and often it is the ones who most need our attention who are never noticed at all. Yes, I am grateful for my good fortune in how and where I live, that I can share these stories of the appreciation of books and art, but I also feel ashamed. I am a generally happy participant in a system that gives so much to a relative few of us while also trampling people who only need the simplest of resources that are utterly denied them. We could meet everyone’s needs. We choose not to do so.

Also as of two days ago, many people on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota were cut off from supplies and have gone so far as to burn clothing in stoves in an effort stay warm. There is a story about this, with links to donate for aid, HERE. Please consider helping out. If not on behalf of the folks at Pine Ridge then maybe somewhere closer to your home. I like to think that is part of why we come together here too.

The house across from mine sold last summer but no one is living there now. It is empty. Who could use that shelter? Why is it so easy to forget people, or not care in the first place to know we are forgetting? These are the questions I am pondering as the year rolls over. Time is short.

It’s full dark beyond my window. There was a brief glimpse of blue sky before sunset but the clouds rallied and now the wind is lashing the glass with hard rain. The beautiful snow of just a couple days ago is turning to slushy muck. It’s 41° outside.

Poetry as Spiritual Practice

Friends, there are still two spaces available to join my “Poetry as Spiritual Practice” workshop online through Poetry Forge. You may register HERE. I’d love to see a couple more of you there. If you really, really want to do it but can’t afford it, CONTACT me and maybe we can figure something out, if time and space allow….

And Finally….

I’ve shared this before but it’s worth repeating. This is the John Haines poem that is represented in the title of John Luther Adams’s memoir I mentioned. I love it. That last stanza clouds my eyes every time. And tonight, especially….

Miigwech, as ever, for reading, my friends. I hope you are staying warm and have the happiest, happiest of New Years.

😂

This friend has an excellent book that just came out last summer called This America Of Ours: Bernard and Avis DeVoto and the Forgotten Fight to Save the Wild and I urge you to consider adding it to your personal library in the Science and Conservation Essentials section.

As I write, I am listening to Adams’ atmospheric 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Music and 2015 Grammy Award for Best Classical Contemporary Composition winning piece, Become Ocean, which is magnificent. With my computer monitor dimmed as much as I can abide, besides the fading light of evening out the window to my left I’m burning two beeswax candles and a smelly candle whose scent is called, “Mountains Cold.” Sometimes I go all out for you people.

Thank you-for this piece and all the ones that came before. I always look forward to seeing them in my inbox. And happy new year to you as well - may it be filled with just the right amounts of whatever it is you need the most, be it warmth, a chilly saunter through fog, or reasons to pause editing to witness a bit of life that needs witnessing (and everything in between). :)

From my commonplace book: "The lostness and sinking of things, so close to the ordinariness of our lives. I was mending my salmon net one summer afternoon, leaning over the side of my boat in a broad eddy near the mouth of Tenderfoot. I had drawn the net partway over the gunwale to work on it, when a strong surge in the current pulled the meshes from my hand. As I reached down to grasp the net again I somehow lost hold of my knife, and watched half-sickened as it slipped from my hand and sank out of sight in the restless, seething water." ... Always glad to see Haines get more attention. His work has been a touchstone, over and over, for decades.